Research Notes: Newspapers And Netflix

Netflix might well replace cable TV. But is that enough to hold the stock?

(Author’s note: Here in the New Year (and based on your feedback) we are making some changes to the way we publish our midweek Research Notes. Instead of the usual broad-based coverage we will be covering more thematic and single ticker analysis. Think deep dives but not necessarily buy/sell recommendations. We hope you enjoy the new and slightly altered format.)

📍 TLDR:

The collapse of the newspaper business provides an interesting paradigm for streaming media in a “cord-cutting” world — particularly for Netflix.

NFLX bulls believe that Netflix is the core beneficiary of cord-cutting. But what if, like newspapers, there are no winners?

Quantitatively and qualitatively, the bear case for Netflix stock needs to be considered.

It’s difficult for investors under, say, 45 to appreciate the incredible strength of the newspaper business model in the pre-Internet age. In many markets, the local newspaper had a monopoly. Even in large cities like Chicago, a duopoly reigned.

Much of daily life needed to go through those newspapers. Businesses of all sizes used the classified section to find employees. Without Zillow Z 0.00%↑ and its ilk, the real estate market relied on print listings. In most jurisdictions, public notices were (and still are — for now, anyway) required by law to be printed in major local papers.

Relative to mature modern tech companies, newspapers were not quite as profitable. In the Berkshire Hathaway shareholder letter from 1983, Warren Buffett noted that the Buffalo News, owned by Berkshire, had “somewhat exceeded” a targeted net (ie, after-tax) margin of 10%, with margin performance “about average” for the industry.

But the equity market then was much more heavily tilted toward old-line, lower-margin sectors like manufacturing and industrials. In that kind of market, the combination offered by newspapers of double-digit net margins (and potentially higher free cash flow margins, given the delta between depreciation and capex) and competitive dominance made the sector attractive.

Indeed, for these reasons newspapers were attractive to Buffett himself. In 1977, The Washington Post Company and Knight-Ridder Newspapers combined accounted for more than 20% of Berkshire’s equity portfolio. That same year, the insurance giant spent $34 million — more than 20% of its book value at the time — to acquire the Buffalo News, which it would own until early 2020.

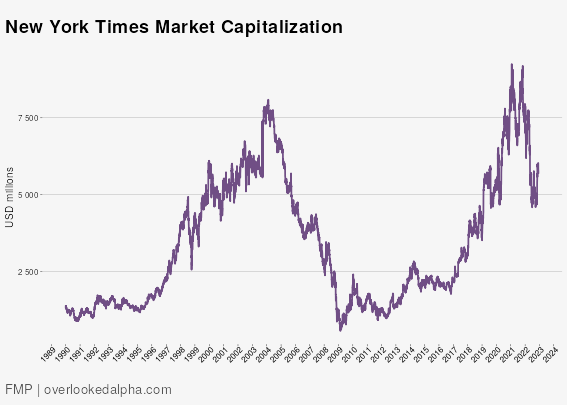

Obviously, the Internet blew up the old-line newspaper business model. In the digital age, the New York Times Company NYT 0.00%↑ has been probably the most successful business in the industry. Its market capitalization is down by roughly one-third since the beginning of 2000. Even on an adjusted basis, and with the benefit of digital subscriptions and substantial cost-cutting, net margins are below the 10% target Buffett cited 40 years ago.

And that’s the best business of the group. Lee Enterprises LEE 0.00%↑ stock has declined over 90% during the same period. McClatchy, which merged with Knight-Ridder in 2006, filed for bankruptcy in 20201. USA Today publisher Gannett GCI 0.00%↑ merged into New Media, with the combined company keeping the Gannett name; that tie-up has not worked out. In 1983, the Washington Post Company had a market cap of nearly $500 million. Amazon.com AMZN 0.00%↑ founder Jeff Bezos bought the paper 30 years later for barely half as much (and likely would struggle to break even on the deal today).

It’s not surprising that, in the digital age, newspapers have struggled. What is perhaps surprising is that digital print media companies, which ostensibly have replaced newspapers, haven’t come close to recreating the dominance of their offline predecessors.

To be sure, some investors might argue that social media companies like Meta Platforms META 0.00%↑ unit Facebook and even Twitter are the new publishers or that the dominance of Alphabet GOOG 0.00%↑ GOOGL 0.00%↑ in search is a global version of the local newspapers’ pre-Internet monopoly on information.

But in terms of the actual media business, of creating revenue by sourcing that information (rather than sharing or surfacing it), there’s been no replacement for the old model. What is left is a fragmented, low-margin industry with minimal scale and often a race to the bottom in employee compensation (and count). Including dividends, shareholders in NYT are down 8% since the beginning of 2000 — and in the context of the sector that very much feels like a win.

Indeed, few pure-play digital media companies have even scaled to the point where they can go public. Two that went the de-SPAC route — BuzzFeed BZFD 0.00%↑ and Marketwise MKTW 0.00%↑ — are both down 80%-plus from their merger price2. The $34 million Berkshire paid for the Buffalo News in 1978 is equal to about $155 million today — and that was a good price Berkshire paid. Yet in a global Internet age, there simply aren’t that many digital properties in the U.S. now worth what a single monopoly paper in a mid-sized city with a declining population was valued at 45 years ago, let alone the ~$1.5 billion (in today’s dollars) at which the public markets valued The Washington Post Company.

From a moral or political perspective, the end of newspaper dominance may not be a bad thing (and it would be stunningly hypothetical to argue otherwise on a Substack!), but purely in terms of economics, the news industry clearly has changed for the worse.

Cord-Cutting

There are some obvious similarities between what happened to print media starting in the 2000s and what happened to video beginning in the mid-2010s. To be sure, the parallels are not exact. Most notably, print media lost control of distribution (one reason why newspaper publishers have been so critical of Facebook). In contrast, in streaming media, control of distribution has actually returned to content owners from cable and satellite operators.

But from the perspective of the consumer, the respective transformations are much more alike than different. In both cases, the amount of content has simply exploded. That explosion in turn has led to fragmentation, since media consumers are no longer left with the choice of widely-distributed, mainstream content (whether a Dave Barry column or a mediocre sitcom sandwiched between Seinfeld and Friends) or no content at all.

In both print and video, the number of commercial outlets has risen dramatically. On top of that, individuals have been empowered to create and importantly, market, content in a way that simply wasn’t possible 25 years ago. That trend, too, applies regardless of medium: Substack, Twitter, or YouTube in their own way all contribute to this massive explosion of content.

The New Newspapers

At the beginning of last month, we talked at length about the challenges facing streaming media companies. The core problem is simple: even relatively large content providers still have a dangerous reliance on revenues from legacy linear networks.

Returning to our newspaper parallel, Warner Bros. Discovery WBD 0.00%↑ and even Disney DIS 0.00%↑ are the Knight-Ridders and McClatchys of video. The sheer brilliance of the pre-cord-cutting model for ESPN, in particular, remains underappreciated. Thanks to affiliate fees paid by cable and satellite companies, Disney got roughly $100 per year from nearly every household in America whether they watched the network or not. Those households that did watch added a few dollars more per month in per-subscriber advertising revenues.

The new world simply isn’t as profitable, for ESPN or for every other network that benefited by getting revenue from cable and satellite subscribers who didn’t want that network. There was no a la carte offering. No one subscribed to Discovery to watch “Shark Week” and then canceled two weeks later. In fact, no one subscribed to Discovery at all. They subscribed to cable — to all of cable.

Just as newspapers benefited from being the only game in town for print content, networks benefited from being essentially3 the only source of in-home video content. And just as newspapers have been crushed by an explosion of competition, both corporate and individual, for-profit and non-profit, the same is true for networks in a world with YouTube and Twitter and TikTok and a staggering number of streaming apps.

The Big Winner Is Netflix

Perhaps the biggest beneficiary of cord-cutting, of course, has been Netflix NFLX 0.00%↑. As a streaming-native operator, Netflix disrupted the industry and jumped out to a massive lead in subscribers. As of September 30, Netflix had 223 million subscribers worldwide, a figure topped only by Disney at 235 million (albeit across multiple brands, including ESPN and Hulu).

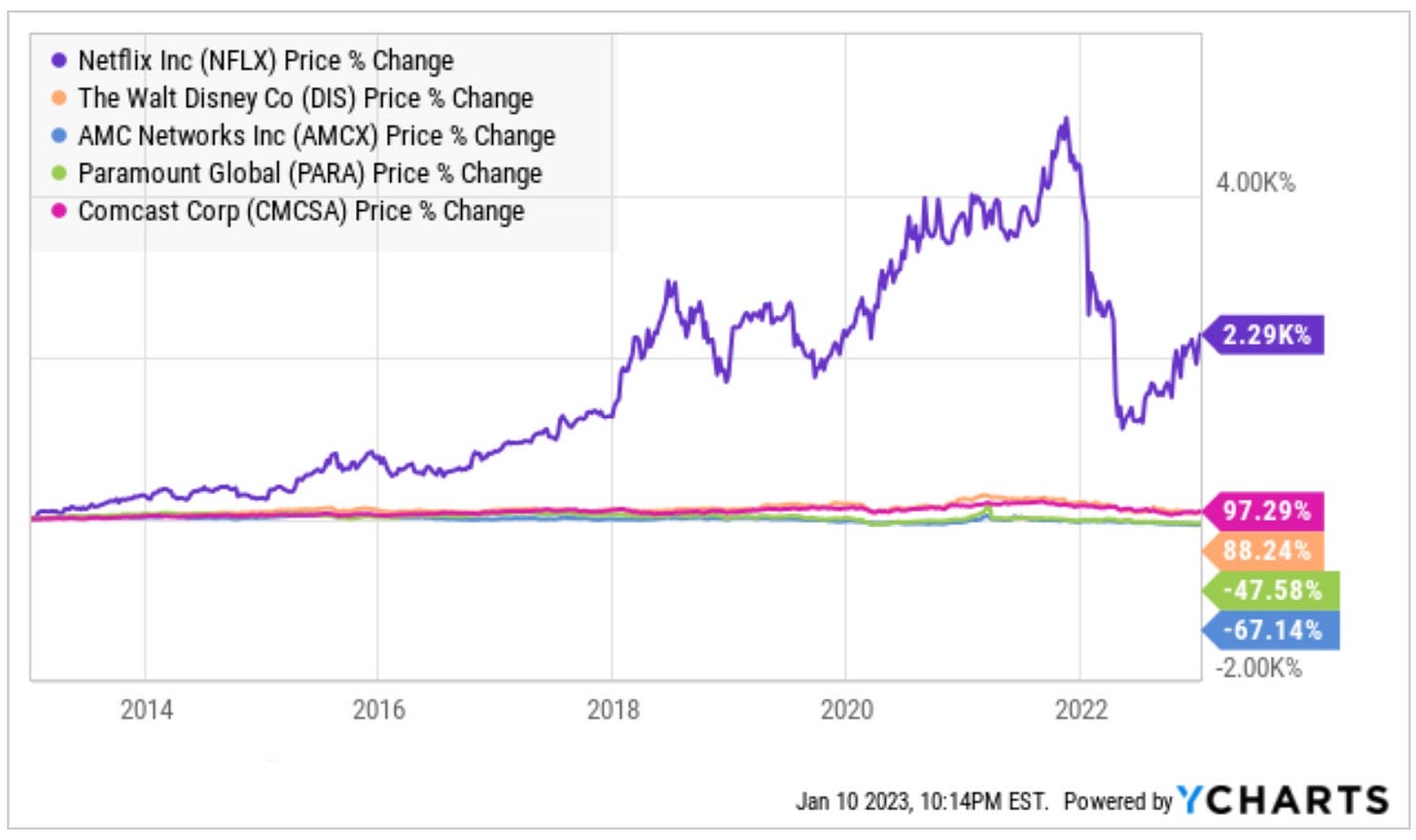

That massive subscriber base has led Netflix to a market cap near $150 billion. Per YCharts, the stock has returned 27,200% since its 2002 initial public offering, more than 30% annualized for over two decades. Ten-year annualized returns are even better, at 37%.

That performance is more impressive in the context of the sector:

source: YCharts

It’s not just the stock. In 2022, based on analyst consensus, Netflix should generate something like $4.5 billion in profit.

Every piece of evidence we have — every single piece of evidence — tells a simple story. The cord-cutting revolution has one single and huge winner: Netflix.

The Debate Over Netflix

Even bears don’t really argue with that case much. They did at one point, certainly, as witnessed by the famous 2010 letter from Netflix chief executive officer Reed Hastings to vocal NFLX short Whitney Tilson:

At this point, the bear case for Netflix rests in part on an argument over valuation. On its face, NFLX doesn’t look that expensive, at a little over 30x expected earnings per share for this year.

But there is an enormous, and to this point consistent, difference between Netflix earnings and the company’s free cash flow. That difference centers on the company’s content costs.

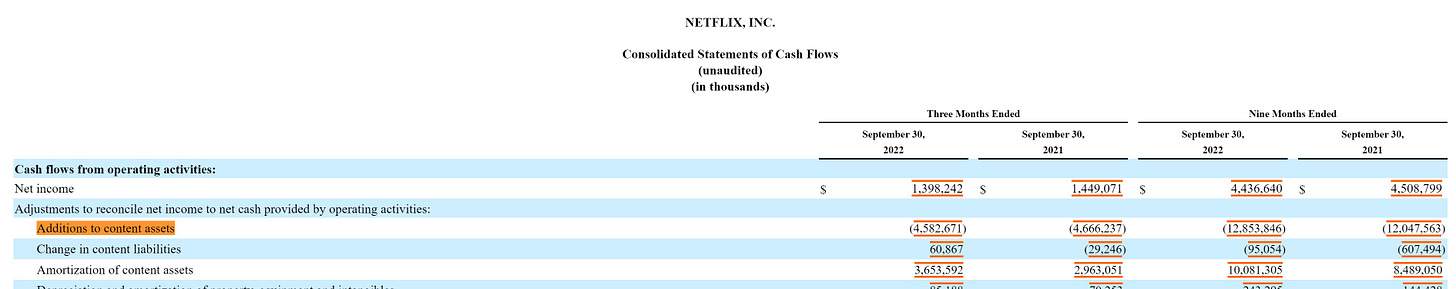

In its free cash flow statement, Netflix books the actual cash spent on content in a given year under the line item “additions to content assets”:

source: NFLX Q3 2022 10-Q

In its earnings statement, however, Netflix amortizes that content (on the cash flow statement that non-cash amortization is added back to net income, with the actual cash spend deducted).

This isn’t an accounting trick or anything questionable; it’s simply the difference between what earnings mean and what cash flow is. Netflix investor relations even has issued a presentation [PDF] discussing its accounting practices.

The reason for amortizing content is that content produced in a given year has value beyond that year. For most of its content, over 90% of the cost is amortized within four years, and on an accelerated basis (see p.27 of the 2021 10-K for the discussion).

The gap between cash spend on content and amortization of that content is significant: it averaged over $3 billion in 2020 and 2021 (with the individual years impacted by the pandemic) and is tracking toward $3.5 billion-plus this year.

Again, relative to earnings NFLX looks reasonably valued at ~32x or so, depending on how exactly Q4 plays out. Relative to normalized free cash flow, however, the multiple clears 100x.

This quantitative gap reflects a qualitative debate. The short case here (and there’s still ~$3.5 billion in capital backing short trades in NFLX) is not just that the stock trades at 100x-plus free cash flow. It’s that free cash flow is the metric that really matters.

The argument for trusting earnings, and its amortized content costs, is a) that the content has significant value that lasts for a period of years and b) that eventually, amortization and cash spend will converge. This requires that growth in cash spend get to or near zero; a few years after that point, the two metrics should be roughly equal.

The argument for focusing on free cash flow, however, is that the two metrics won’t converge. Because for the metrics to converge, content spending growth has to decelerate markedly. Bears focus on free cash flow not because that metric is ‘better’, but because they believe that deceleration can’t happen.

The Short Case for Netflix

At this point, it’s impossible to definitively argue for either an earnings- or cash flow-based approach to valuing Netflix. That in turn makes it difficult (though not impossible) to get too aggressive in shorting NFLX stock. Quarterly earnings reports — notably on the subscriber front — are going to move the stock much more, and much more quickly, than the predictions of what cash content spend looks like in 2026.

But the history of print media does suggest that the short case has some merit. There seems a belief that since Netflix (and Disney) has built up a massive subscriber base, it’s a great business. That’s not necessarily the case. Netflix no doubt has a better business than its rivals that are trying to pivot from their linear businesses, but just like the print business the video business is not as good as it used to be.

It’s certainly not like cable. Revenue suffers from a la carte pricing, easy cancellation and renewal, and no need to actually be a 12-month-a-year subscriber. (Inflation and, in some markets, recession will likely provide pressure on this front in the near term.)

Those factors all conspire to keep costs heading higher. Netflix can’t rest on its laurels or even suffer through a short-term period of disappointing original content without risking a quick increase in churn.

We’re already seeing some evidence for the bearish perspective. Amortization for produced (ie, original) content has skyrocketed, more than doubling between 2019 and 2021 and then rising more than 50% year-to-date. Licensed content amortization now is just 57% of the total year-to-date, which means that cash spend is probably 50/50 original/licensed.

Licensed content spend probably can flat-line, as Netflix maintains a decent library of content produced elsewhere. But in a competitive space, at the moment the company’s original content seems like it needs to be more (in amount and in cost).

Indeed, the company’s decision to move into advertising (something Hastings long had dismissed) seems a potential admission that the subscription model can’t quite work the way that bulls hope.

There’s an argument that Netflix’s content spend is rising simply because rivals are spending. Some of those rivals will fade away and the industry will normalize. Netflix won’t need to spend $17 billion annually, as it plans to do this year.

But that argument looks a bit too narrow. Competition is not just Disney and HBO Max; it’s YouTube and TikTok, as Hastings himself has said in the past.

There is so much content out there that it seems exceptionally unlikely that Netflix can ever start to coast. There’s simply no coasting left anywhere in the media world. And if that’s truly the case, NFLX will be a winning short — at some point.

As of this writing, Vince Martin has no positions in any securities mentioned. He formerly had a business relationship with Marketwise.

If you enjoyed this post please do us a favor and click the heart button ❤️

Disclaimer: The information in this newsletter is not and should not be construed as investment advice. Overlooked Alpha is for information, entertainment purposes only. Contributors are not registered financial advisors and do not purport to tell or recommend which securities customers should buy or sell for themselves. We strive to provide accurate analysis but mistakes and errors do occur. No warranty is made to the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information provided. The information in the publication may become outdated and there is no obligation to update any such information. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a loss of original capital may occur. Contributors may hold or acquire securities covered in this publication, and may purchase or sell such securities at any time, including security positions that are inconsistent or contrary to positions mentioned in this publication, all without prior notice to any of the subscribers to this publication. Investors should make their own decisions regarding the prospects of any company discussed herein based on such investors’ own review of publicly available information and should not rely on the information contained herein.

The novel coronavirus pandemic was a factor in the timing of the filing, but not the cause. McClatchy stock and bonds had priced in a high risk of bankruptcy for most of the 2010s.

It’s actually a stretch to even put MarketWise, the publisher of InvestorPlace, Stansberry Research, and other investor-focused content, in this discussion centered on the replacement for newspapers. But that’s kind of the point — there are so few major replacements for newspapers to discuss.

There were DVDs and VHS tapes, yes, but for the overwhelming majority of consumers they were complements to rather than replacements for cable television, in particular.

Nice writeup on the pros/cons of Netflix.