Research Notes: Sum Of The @#$*&! Parts

The risks and rewards of SOTP cases, plus commentary on two current plays

📍 TL;DR

Sum of the parts cases have earned a reputation for being more often value traps than value plays.

But in many cases, the problem is investor analysis, rather than the basic structure of the thesis.

We detail the pros and cons of the SOTP approach.

Then we take a look at two of the more interesting SOTP cases at the moment.

(Author’s note: Get comfortable, and stay hydrated — this is a long one!)

Sir John Templeton famously argued that the four most dangerous words in investing are “this time it’s different.”1 One of the greatest fund managers of all time was no doubt correct, which is why his pithy remark is so widely quoted. But many investors would suggest a phrase as the second-most dangerous: “sum of the parts”.

In recent years, SOTP cases have developed a reputation of working on paper but rarely in practice. Of course there is even a meme:

But there is an argument that the skepticism toward SOTP cases is somewhat overwrought. I’ve personally had some success, for instance doing well on Dell Technologies DELL 0.00%↑ before it spun off VMWare VMW 0.00%↑ and making a profit on Cannae Holdings CNNE 0.00%↑ around the same time. (As we’ll see momentarily, I’ve also had some failures.)

An SOTP thesis is not inherently flawed. It can work, and often does work. The catch, however, is that a sum of the parts model seems so simple. That simplicity can blind investors to the type of mistakes that can be made with any bullish thesis.

In that context, we’ll take a look at the more interesting SOTP stocks out there at the moment. But first, we’ll look at the potential perils of these models, as highlighted by a few examples.

The Parts And The Sum

One of the simplest ways to get SOTP wrong is simply to get the value of the parts wrong. The aforementioned CNNE is an excellent example of this effect — both positive and negative.

Cannae was split off from Fidelity National Financial FNF 0.00%↑ as a tracking stock in 2014, and became fully independent three years later. At the time, Cannae's most valuable asset was a stake in software developer Ceridian CDAY 0.00%↑. Ceridian went public in 2018, and like so many other software stocks at that time performed exceptionally well. CNNE went along for the ride:

source: YCharts. chart from April 2018 to Jan. 1, 2020

Cannae has steadily sold off CDAY shares (though it still owns almost 4% of the company). In 2019, it used some of the cash generated to join a consortium that took business data provider Dun & Bradstreet DNB 0.00%↑ private in a leveraged buyout. (To be clear, that acquisition was not a result of empire-building, but rather reflected Cannae's core strategy from the jump. The company essentially is supposed to be an investment manager, to the point that executive compensation is largely based on investment returns clearing a hurdle rate.)

D&B triumphantly returned to the public markets less than 18 months later. Cannae owns 18% of the company, which by its own calculations accounts for roughly one-third of net asset value:

source: Cannae Holdings investor relations

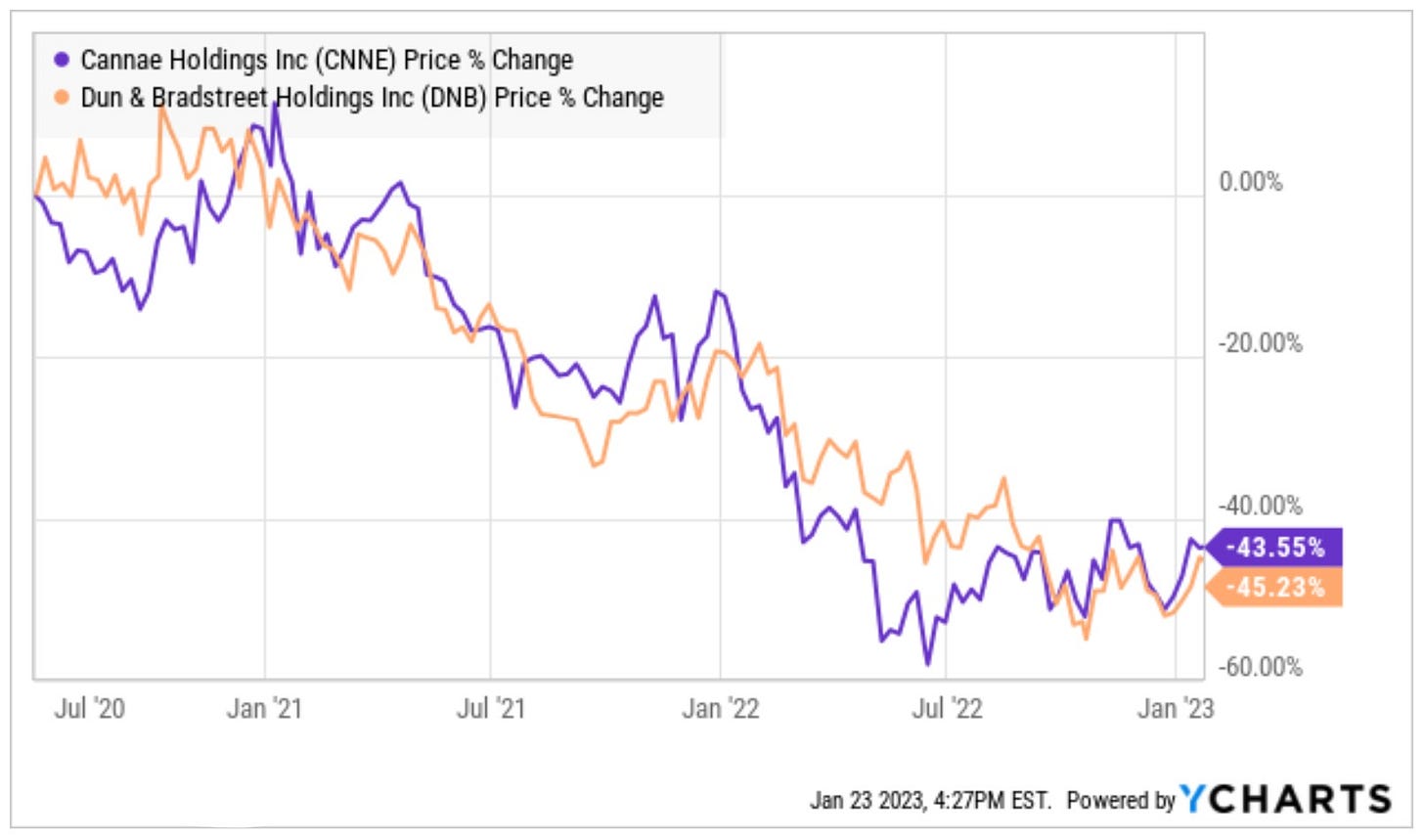

But a now-leveraged DNB has tanked in a more nervous market. Just as CDAY brought CNNE up, DNB has done the opposite:

source: YCharts. chart since 6/30/20

From here, the size of the sell-off in CNNE appears overdone. Cannae’s public investments have all declined, certainly, but the discount to NAV (now over 40% even when including taxes on gains and management fees) is dramatically wider than it’s been in the past. Of course, that discount only helps if the stocks making up that NAV perform better than they have over the past 18 months.

The Management Question

VOXX International VOXX 0.00%↑ includes several businesses. Its most valuable holding is well-respected audio manufacturer Klipsch. It also has an automotive division that makes products including headrest televisions. There's a biometrics startup called EyeLock. VOXX owns 50% of a joint venture in an electronics distributor that serves the marine, recreational vehicle and other end markets. Finally, there's a declining consumer electronics business that dates to a time when the company, then known as Audiovox, distributed alarm clocks, remote controls and other products that are increasingly obsolete.

I’ve followed VOXX closely for nearly a decade now, and for essentially that entire time the stock has traded at a significant discount based on any reasonable SOTP model. (Admittedly, even the paper case got a bit dicey in early 2021.) The actual math might differ depending on the share price and recent results. But the conclusion is always along the lines of “Klipsch alone supports the enterprise value of the entire business” or “investors get the ASA stake for free, which suggests 60% upside”.

Unfortunately, for that entire period VOXX has been run by executive chairman John Shalam and chief executive officer Pat Lavelle. And neither man has shown any real interest in catalyzing the value that exists on paper — a significant problem since Shalam has controlling voting power due to a dual-class structure, while Lavelle is incredibly close to and loyal to his boss.

For Shalam, who founded the company in 1960 (yes, 63 years ago), there’s no doubt some personal reluctance to sell the company he built. Lavelle may have the standard incentive problem of all corporate managers (particularly those without significant shareholdings), in that creating profits for shareholders may destroy a revenue stream for himself. But at this point, their ages might suggest a desire for an exit: as of the proxy statement last June, Shalam was 88 and Lavelle 70.

(As an aside, chief financial officer Charles “Mike” Stoehr is 76, and has been CFO since 1978!! There are multiple CFOs at Fortune 500 companies who were not alive when Stoehr took the job. Seriously, guys, just sell the bleeping company already.)

These kinds of roadblocks are a common problem in SOTP cases. But to our earlier point, they’re a common problem in value investing in general.

Imagine a company that, say, has cash on its balance sheet that is equal to its entire market capitalization. Is that a good thing? Many investors would say ‘yes’ — but it’s far from guaranteed to be the case. What plans does management have for that cash? Is there a track record of returning corporate cash to shareholders, and/or focusing on shareholder value? If not, what value does that cash actually have2?

Whatever the fundamental value inherent to a stock, it’s always up to management to get that value to shareholders. It doesn’t really matter whether that value comes from an owned operating business or a corporate bank account.

Unfortunately, there is no shortage of management teams who don’t necessarily merit the trust that they will turn paper value into actual returns. And investors always need to understand that fact. Doing otherwise is like sitting at a poker table with a calling station, trying to bluff, and then getting angry when the opponent calls with fifth pair.

Structural Problems

But VOXX highlights another potential complication as well.

Management concerns are real, to the point that there have been uncomfortable, public exchanges between executives and shareholders demanding buybacks and other strategy changes. That frustration makes sense: there is value to unlock here. But there’s also not really a great path for VOXX to take.

From a pure value perspective, the most logical thing for VOXX to do would be to sell Klipsch. That business is the biggest and most valuable, and has a number of potentially interested buyers. But a VOXX without Klipsch is probably EBITDA-negative, and almost certainly has no business being on the public markets. So if the company wants to sell Klipsch, it basically has to sell the rest of itself too.

VOXX perhaps could sell ASA, though it would have to find a buyer for a 50% stake in a relatively small electronics distributor. It could then use the cash to buy back stock, but nearly 40% of shares are owned by two shareholders3 which means a major share buyback would impact liquidity and (unless VOXX did a tender offer) likely result in the repurchases themselves moving the stock higher (and thus creating a price for later buybacks likely above 'true' fair market value).

There are other options that might be reasonable — a management-led LBO, a cash dividend — but the broad point is important: companies simply don’t make dramatic moves all that often. Some of that is management reticence (whether to take a big swing or to lose their jobs); some of it probably is simple inertia and risk aversion.

There’s some logic to the preference for the status quo: change is not only scary, but expensive. For years, shareholders in Gap Inc. GPS 0.00%↑ (myself included) wanted the company to spin off Old Navy, which in the 2010s was not just the best business in the portfolio but one of the better businesses in retail4.

In February 2019, Gap finally announced that it would indeed spin off Old Navy. The market cheered — for a single trading session.

The problem quickly became clear: the spin was going to cost the company a fortune. Gap Inc. estimated cash costs of $300-$350 million for the separation, and annual “dis-synergies” of $90 to $110 million — a figure that included efforts to find cost savings elsewhere.

It’s tempting to make the cynical argument that the only companies that break up are large enough to generate material investment banking fees for Wall Street banks. But even for a mid-sized company (Gap had a market cap of ~$10 billion in early 2019) the costs of splitting up are material.

Indeed, for Gap, those costs proved to be one of the core reasons why the separation eventually was abandoned. For even smaller companies, the problem is even greater.

Creating two public companies creates duplicate costs which are material against a relatively small earnings base. Selling a business unit creates transaction costs and, often, taxes which investors can fail to account for in their SOTP models. And that business unit, owing to dis-synergies or the simple disruption that can be caused by a change in ownership, is usually worth less outside its existing home than within it.

Are They Really Parts?

Amazon.com AMZN 0.00%↑ is one of the mega-cap companies that commonly is valued using an SOTP model. The fit seems perfect, given Amazon's reach across Amazon Web Services, its Prime and advertising revenue streams, and retail sales through an owned online operation, third-party sellers, and physical stores (including Whole Foods Market).

Here, for example, is a 2018 SOTP model from the investment firm Jefferies, which put a 2021 price target on AMZN of over $3,000 per share ($150 adjusted for the 20-for-1 stock split last year):

Jefferies would update the model in early 2021, and assign a price target of $5,700, or $285 post-split. That’s just shy of triple the current price of $97.

With all due respect to the Jefferies analyst, there is a pretty significant problem here: Amazon’s “parts” aren’t really “parts”. The retail business, subscriptions, and advertising are all part of a single operation. Decisions about pricing or the intensive capital spend on logistics absolutely are influenced and informed by the high-margin revenue coming in from Prime and from advertising.

It’s not a perfect comparison, admittedly, but these SOTP cases are somewhat akin to arguing that Costco Wholesale COST 0.00%↑ has upside because the actual retail business can become more profitable. (Membership fee revenue accounts for more than half of Costco's operating profit; operating margins in the retail business are in the range of 2%.)

But, of course, that's not how the Costco business model works. Customers buy memberships in large part because the goods are priced in a way that Costco makes minimal profit. The issue with separating Prime and the third-party marketplace and the owned online stores, even ignoring the problem that they can't be physically separated, is that it’s not how the Amazon business model works, either.

Little (Big) Math Mistakes

The final group of SOTP errors comes from simply missing relatively significant costs.

Again, for small caps, friction costs can be material. Transaction costs can matter. Negotiating leverage can be an issue: trying to sell a business for, say, $50 million can result in a small group of buyers. And if the seller already has held a public conference call to discuss a strategy that includes selling that business, they’ve instantly created a buyer’s market for the asset.

Taxes matter. Last year, we covered Spectrum Brands SPB 0.00%↑, which is facing antitrust scrutiny as it attempts to sell its largest business unit. Even assuming the deal goes through, Spectrum expects to pay some $800 million in taxes and other adjustments to gross proceeds for the sale.

And, importantly, corporate costs matter. We’ve seen plenty of SOTP cases that use segment-level performance to value each operating unit, and then fail to capitalize corporate costs.

Those costs are real. And unless the company actually plans to break up — which, again, simply does not happen that often — they’re ongoing, and need to be incorporated into the valuation model. (Even in a scenario where the company does break up, the buyer will presumably have some type of added overhead which in turn will affect the price it is willing to pay.)

But, again, investors can make these kinds of mistakes on any investment. It’s easy to value a tech company on EV/EBITDA, and ignore capitalized software development costs (an accounting decision which moves those costs out of operating expenses, thus inflating EBITDA). A business can look cheaper than it is on a price to free cash flow basis because, for instance, net operating loss carryforwards are temporarily pushing cash taxes to zero.

These errors aren’t unique to the SOTP model, but investors using those models probably are more susceptible to them, simply because the end result of the model can look so elegant. A nice, neat table of Assets A through E, which have a total per-share value 50% above the current stock price, ‘feels’ a little better, and a lot more exact, than “hey, this is valued at 13x free cash flow and look at peers.”

And so investors don’t necessarily need to junk the SOTP method; rather, they (and we!) should make sure to be quite careful when using it.

IAC/InterActive Corp.

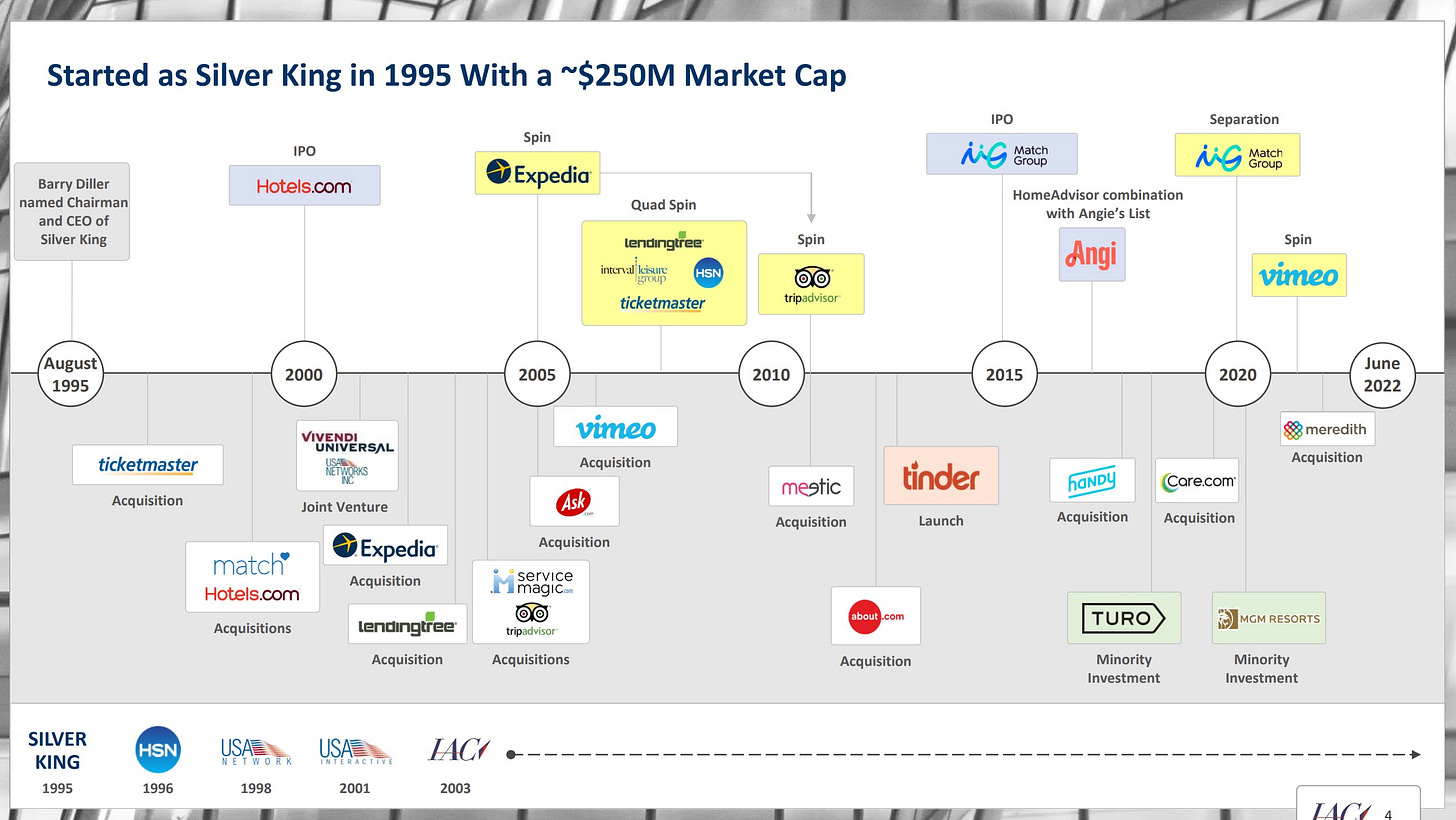

IAC/InterActive Corp. IAC 0.00%↑ is probably the purest SOTP play out there at the moment. Since its founding in 1995, IAC has bought, built, and spun a large number of well-known digital businesses:

source: IAC presentation, June 2022

As of June, that original $250 million market cap had turned into, by IAC’s calculations, more than $60 billion in equity value. That latter figure is probably modestly lower now, but the broad point is that IAC has created real, material shareholder value for close to three decades.

The market is skeptical that trend is going to continue. Even with a strong rally so far in 2023 (IAC is +22% already), shares are down ~two-thirds over the last 20 months. On paper, however, the current $54 per share price is a gift.

At Wednesday’s close of $54.30, IAC has a fully diluted5 market cap of $5.26 billion. Net debt at the corporate level at the end of Q3 was $233 million (pro forma for the $50 million sale of Bluecrew, which occurred after quarter-end), for an enterprise value of $5.5 billion. (We're excluding net debt from subsidiary ANGI Inc. ANGI 0.00%↑ , since that balance sheet is reflected in the ANGI stock price.)

IAC owns 425 million shares of ANGI, worth $1.2 billion at Wednesday’s close. It owns 16.9% of MGM Resorts International, which is another ~$2.5 billion.

Those ‘parts’ seem pretty easy to value, given both are publicly traded, and leave the remaining assets with an effective value of $1.8 billion.

It seems relatively easy to get to that point, and then some. IAC owns a 26.7% stake in car-sharing platform Turo (plus warrants). Turo has filed an S-1 ahead of a possible IPO; the most recent amendment shows trailing twelve-month revenue of ~$700 million, with 200%-plus growth in 2021 and a 69% increase in revenue through the first nine months of 2022. TTM Adjusted EBITDA is ~$72 million (with a modest decline YTD 2022).

Even in a bear market (the likely reason why Turo hasn’t gone public yet; the company originally filed last January), it’s not difficult to get to a roughly $2 billion valuation here, at ~3x revenue and ~30x EBITDA. Very roughly (and probably conservatively), that values IAC’s stake in Turo at $500 million at least.

Meanwhile, IAC — which, again, has a very strong track record in capital allocation — spent $500 million to acquire Care.com in February 2020, and $2.7 billion to pick up publisher Meredith, owner of People, Better Homes & Gardens, Investopedia.com, and other properties, the following year.

Assume those assets are valued at half what IAC paid and we’re now to an SOTP valuation of $5.8 billion ($3.7B for the publicly traded companies + $0.5M for Turo + $1.6B for Meredith and Care.com). There’s a search business (centered around engine Ask Jeeves) which has generated $100 million-plus in EBITDA over the past four quarters; that should be worth at least $600 million at a conservative 6x multiple. Other assets including The Daily Beast, app developer Mosaic, and employment platform Vivian Health — which grew revenue 77% in Q3 — have some value as well.This loose and seemingly conservative model suggests at least 20% upside, with EV at ~$6.5B and market cap at $6.3B against the current $5.26B.

But in fact, looked at another way it’s actually much tougher to make the case for IAC here.

One issue is that we haven’t yet mentioned corporate costs, which run at ~$90 million annually. Capitalize that at a reasonable multiple and most of the paper upside disappears.

But the broader issue is that the company, across multiple businesses, has been pressured significantly by the recession in online advertising. Whether that recession has been driven by policy changes at Apple AAPL 0.00%↑ or the broader economy or both is up for debate, but IAC has taken a hit.

Dotdash Meredith's TTM Adjusted EBITDA, even backing out restructuring and transaction costs (IAC leaves those costs in), is $196 million. That's a huge disappointment given that the company guided for 2023 Adjusted EBITDA of $450 million from the business. Search Adjusted EBITDA dropped 36% year-over-year in Q3 after a stable first half.

Excluding Angi, trailing twelve-month Adjusted EBITDA is $210 million (again, adjusting for one-time factors at Dotdash Meredith). Valuing Turo at $500 million, then, IAC is trading in the range of 6x EBITDA, with ~two-thirds of that profit coming from digital publishing.

That’s fine as far as it goes, but it doesn’t quite seem compelling. That’s particularly true because so much of the enterprise value comes from easy-to-value parts; it takes real upside in the more uncertain valuations to suggest IAC has material upside on a consolidated basis.

There was a price (and, in retrospect, a month ago there was a price) at which this collection of assets was intriguing. We’re not sure $54 is it, however.

INNOVATE Corp.

This article is already long enough, so we won’t reproduce it in full, but we strongly encourage readers to review the corporate description of INNOVATE Corp. On Wednesdsay Chris DeMuth Jr. wrote VATE up over at Seeking Alpha, and correctly called its portfolio "a rando hodgepodge of independent non-cross collateralized assets." DeMuth highlighted the slide from INNOVATE that details just how rando that hodgepodge is:

source: Innovate IR via Seeking Alpha/Chris DeMuth Jr.

INNOVATE is the former HC2 Holdings, which once was led by Phil Falcone, at the time a hedge fund billionaire. Falcone has fallen on hard times, and following an activist effort was pushed out of HC2 in mid-2020.

HC2 (it changed its name in 2021) sold an insurance subsidiary and a chunk of another business, cleaned up its balance sheet, and essentially managed to find some stability. The market has noticed: VATE has quadrupled since early October. But DeMuth makes the case that there’s more upside ahead, with a possible SOTP valuation of $15 to $20 per share against Wednesday’s close just below $3.

As wide as that range is, it only covers a portion of the possible scenarios. INNOVATE’s financial position is stabilized, but still uncertain: the company closed the third quarter with $628 million in debt, and just $5 million of cash at the corporate level. Its 2026 8.5% bonds last traded at 76, implying a yield to maturity just shy of 20%.

As is, VATE trades at ~13x trailing twelve-month Adjusted EBITDA — hardly a value multiple. But that includes ~$30 million in losses in the Life Sciences division, which is aiming to commercialize a pair of transdermal devices (one is an already-approved aesthetic treatment, the other for monitoring of kidney function). Add those back and EV/EBITDA gets below 9x, with zero value applied to the potential upside from Life Sciences.

Because the equity slice remains so small (a bit over one-quarter of EV), valuation here is imprecise. The idiosyncratic nature of the portfolio adds to the uncertainty. DeMuth argues that the embedded call option in Life Sciences is the key source of value. A Value Investors Club post from March 2022 (the piece is paywalled, but an old article is viewable simply by creating an account) in contrast saw the infrastructure business as the key driver of value. Both investors get to a $15-plus per share price against the current $3.

They’re not alone, as the recent rally in VATE (including 110% just over the past month) shows. Valuation questions aside, VATE does seem to check off our boxes. Management is incentivized, with the chairman owning 29% of the company through his fund and personal account. A “poison pill” that aims to protect the company’s tax assets expires at the end of March, suggesting a possible catalyst.

It bears repeating: there are risks here. But this looks like the right kind of SOTP case, and a thesis that could drive triple-digit returns from here if all goes well.

As of this writing, Vince Martin is long shares of CNNE.

If you enjoyed this post you can help us by clicking the heart ❤️

Disclaimer: The information in this newsletter is not and should not be construed as investment advice. Overlooked Alpha is for information, entertainment purposes only. Contributors are not registered financial advisors and do not purport to tell or recommend which securities customers should buy or sell for themselves. We strive to provide accurate analysis but mistakes and errors do occur. No warranty is made to the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information provided. The information in the publication may become outdated and there is no obligation to update any such information. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a loss of original capital may occur. Contributors may hold or acquire securities covered in this publication, and may purchase or sell such securities at any time, including security positions that are inconsistent or contrary to positions mentioned in this publication, all without prior notice to any of the subscribers to this publication. Investors should make their own decisions regarding the prospects of any company discussed herein based on such investors’ own review of publicly available information and should not rely on the information contained herein.

Other sources claim he said, “it’s different this time”, but the point still holds.

I’ve long thought “what is cash on a balance sheet worth?” would be a great question for an interview. The answer obviously is not 100% of face value, even if many investors run the math as such. You wouldn’t pay $100 for a $100 bill in an envelope at some guy’s house if the guy was allowed to give the money back to you when and if he felt like it.

Shalam only owns ~4 million shares, though with the majority of voting power, and a private investor another 5.1 million.

With that brand struggling over the past 4-5 years, that claim might seem outlandish. At the time, however, it wasn’t. Lululemon LULU 0.00%↑ no doubt remains one of the best businesses in retail; back in November, we pointed out the similarities between Old Navy and Lululemon over their first 25 years.

We’re using a 96.8 million share count, based on figures from the most recent 10-Q, which is higher than public data sources suggest.

Excellent article.

As an IAC I want to push back a bit and something I often see with SOTP. You are valuing Dotdash Meredith on current earnings. You noted they are depressed and we are in an advertising bear market. If you look further out (as you would for a normal operating business), there is value there. With IAC, you know that they are going to unlock value via spinoffs - it is their DNA. So if you can withstand the downturn and wait for ad market to turn, they are going to unlock that value. With others stories (CNNE, etc.) you aren't sure.

Great article. I view sum of parts as similar to potential energy - water behind a dam. Absent change, the potential can be inert indefinitely. If undervaluation doesn't convert into earnings growth or meaningful capital return, there is no next buyer of the shares - it will go up if/when SOTP guys get interested, then right back down again when they all try to sell.