The Problem With Mining Stocks

On paper, miners are a strong play for gold bulls. In practice, they've been a disaster

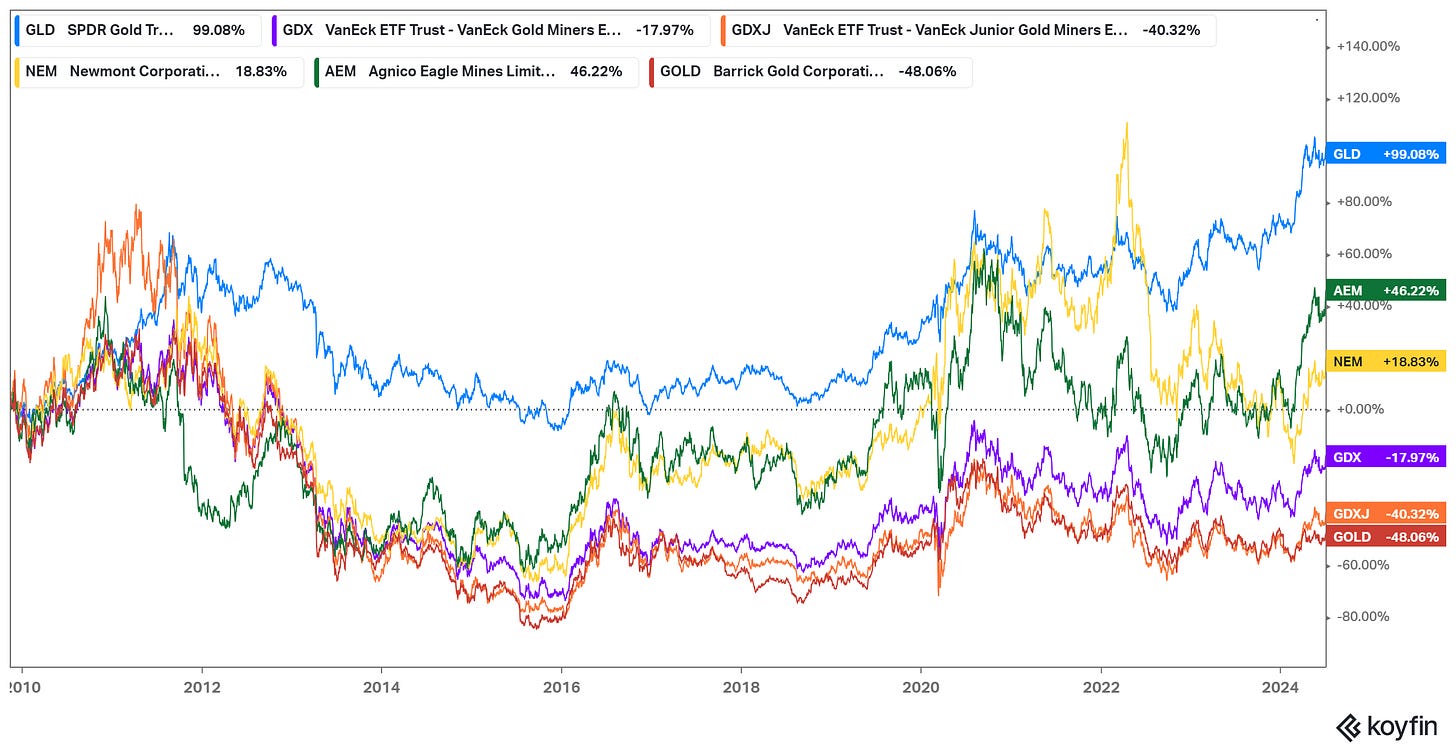

It may not seem like it, but this is an incredible chart:

source: Koyfin

The chart compares the total return since November 11, 2009 of three exchange-traded funds:

SPDR Gold Shares GLD 0.00%↑, a trust which owns physical gold bullion;

VanEck Gold Miners ETF GDX 0.00%↑, which tracks an index covering global gold miners. The three largest miners (Newmont, Agnico Eagle and Barrick Gold) account for nearly one-third of assets and nearly two-thirds go to the top 10. GDX thus provides exposure to the largest miners, the so-called “majors”.

VanEck Junior Gold Miners ETF GDXJ 0.00%↑, which tracks a different index focusing on smaller gold miners. GDXJ was launched in November 2009, which is why our chart begins there.

The reason the chart is incredible is because it tells a relatively simple story: the absolute failure of an entire industry over nearly fifteen years.

Getting Leverage To Gold

Assume that in November 2009, an investor was bullish on gold. He would have good reason: the world was still in the midst of a global financial crisis, U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were ablaze, and uncertainty seemed to reign. All of these factors (financial insecurity, geopolitical strife, a distrust of banks) are among reasons for buying gold.

And so our investor has several options. The simplest is to own gold directly. That could be through physical ownership or through physical ETFs like GLD. If our investor believes gold will go up, it seems wise to own the underlying commodity.

But one issue with gold is that it doesn’t go up that much. Adjusted for inflation, gold has risen less than 300% in a century, real returns of about 1.34% annualized:

source: Macrotrends

Of course, if caught at the right moment (into and out of the end of the gold standard in 1971, or after a decades-long bear market) gold can soar.

But part of the appeal of gold is as “a store of value” which doesn’t necessarily augur the huge potential returns that are possible in equities. For many investors who see gold as a hedge against trouble and not necessarily an investment that should provide huge returns, this is not a problem. But our investor would like to be more aggressive. He wants leverage to the gold price, a trade in which his returns outpace those of the underlying commodity.

Looking To Miners

In theory, gold miners can provide that leverage. Imagine a simplistic model of a miner that can produce 100,000 ounces of gold a year. Its all-in cost to produce and deliver an ounce is $1,500. Its corporate costs are $30 million annually.

At the current spot price of $2,300 (we’re using a round number to keep the math simple), our miner should earn revenue of $230 million per year1. All-in costs are $150 million, creating gross profit per ounce of $800 for an $80 million total. Less $30 million in opex, our miner earns pre-tax profit of $50 million.

If we move the gold price, we start to see the leverage in the mining model. Cut gold by 20%, to $1,840 per ounce, and our miner’s profits are essentially gone: gross profit drops to $34 million, and pre-tax profit to just $4 million. That’s a 92% reduction in profit off a 20% move in the underlying.

Of course, if the price of gold increases 20%, profits soar. At $2,760 per ounce, gross profit per ounce spikes from $800 to $1,260. Pre-tax profit nearly doubles to $96 million ($126 million in gross profit less the same $30 million in opex).

In both scenarios, the underlying stock doesn’t necessarily fall or rise 90%-plus. Investors will base their valuation of the stock on the entirety of future cash flows, which no doubt will include further volatility in the gold price as well as responses by market participants to that volatility.

Notably, the higher price will turn some gold projects from uneconomic to economic; a distant low-grade mine that has an estimated all-in cost of $2,000 per ounce is too risky at a spot of $2,300, but perhaps worth the gamble at $2,800. In addition, private citizens might decide to scrap gold jewelry at a higher price. Both responses increase the supply of gold, and thus (in theory) should reduce the price2.

But, even given those effects, the price of a gold miner should be more volatile than the underlying. So if our investor believes the price of gold will rise, he should be looking to gold miners for bigger returns if his thesis is correct.

Gold Miners Have Failed

This of course is the same kind of operating leverage that we discussed back in December, in explaining the seemingly nosebleed valuations still assigned to growing tech stocks.

But in practice, neither majors nor juniors have provided that operating leverage. Amid nearly 15 years of rising gold prices, both GDX and GDXJ have provided negative total returns. That’s an abject failure to provide the one thing miners are supposed to provide: leverage to the underlying.

What’s relatively stunning about the period is how consistent the failure has been. Over the past twelve months, miners have eked out some outperformance, but not much (GLD +22%, GDX +25%, GDXJ +29%). Across 3-, 5-, and 10-year periods, the ETFs have all provided lower total returns than physical gold.

The same consistency holds across the miners themselves. The three biggest miners, who should have the scale and diversification to manage through varying external environments, haven’t come close to outperforming:

source: Koyfin

On a 10-year basis, Agnico and Newmont have outperformed, but as with the ETFs, there’s been no sign of operating leverage. Perhaps most damning, over 20 years, a position split between Newmont and Barrick would be negative3, even with gold quintupling over that time frame.

So why haven’t gold miners delivered on their potential? There are numerous factors. Mismanagement is one: Barrick’s chairman, John Thornton, has been criticized for years for excessive compensation, and given the performance of Barrick stock no doubt should be.

Gold mining also suffers from geopolitical turmoil and tax-hungry governments. For instance, many miners had to sell Russian assets in 2022. In 2019, Acacia Mining, a Barrick subsidiary, was hit with a $190 billion tax bill (that’s ‘billion’ with a ‘b’) from the government of Tanzania (the firm later settled for $300 million).

Know What You’re Owning

Gold mining is not an easy business. But that’s precisely the point. We have decades of evidence that miners as a whole are not capable of driving the operating leverage their business model should generate in theory.

That perhaps doesn’t mean that every gold miner should be avoided. Streaming play Royal Gold RGLD 0.00%↑, which buys future rights to produced gold, has been a winner. Alamos Gold AGI 0.00%↑, created through a 2015 merger, has outperformed. Juniors have been acquired at premiums that created value for their investors.

But the history of the sector (at the very least) has to create some caution toward entering the space at all. Gold miners need much more scrutiny than just an understanding of reserves and production. Management, capital allocation, and geopolitical risk are all massive factors.

There is a broader lesson here as well, however, which is the importance of not just getting an investing thesis right, but executing correctly on that thesis. We talked last time about Stanley Druckenmiller’s simple thesis on the growth of generative artificial intelligence, which led him to make a hugely profitable bet on Nvidia NVDA 0.00%↑. But an investor could have credibly played genAI growth through other stocks that have underperformed: Augmedix AUGX 0.00%↑, which is using genAI for medical transcription, soared in the second half of 2023 on hopes it could capitalize on the trend, only to plunge 83% this year.

In the bubbly environment of late 2020 and 2021, many investors made incorrect bets on trends, whether electric vehicle growth or the rise of so-called ‘fintechs’ that could revolutionize the banking industry. More than a few compounded those mistakes by owning the tenth-most promising EV manufacturer or a psuedo-fintech with no real differentiation. Missing on the trend meant sharply negative returns, but missing on the execution often led to a loss near or at 100%.

Of course, in this environment, there’s another group of miners that have gained prominence. Bitcoin miners even have their own ETF, the fantasticly-tickered Valkyrie Bitcoin Miners ETF WGMI 0.00%↑.4 Since its launch in February 2022, we see a similar, if not quite as dire story:

source: Koyfin

Bitcoin has risen 29% since WGMI launched and the ETF is -12%. As with Newmont and Barrick, majors Marathon Digital MARA 0.00%↑ and Riot Platforms RIOT 0.00%↑ are lagging badly. Once again, the seemingly simple way to get leverage in theory isn’t quite so simple in practice.

As of this writing, Vince Martin has no positions in any securities mentioned.

Believe it or not, but that “♡ Like” button is a big deal. It signals to new readers that this content is worth reading and it helps us to grow. So if you found value in this post, please give it a quick click!

Disclaimer: The information in this newsletter is not and should not be construed as investment advice. Overlooked Alpha is for information, entertainment purposes only. Contributors are not registered financial advisors and do not purport to tell or recommend which securities customers should buy or sell for themselves. We strive to provide accurate analysis but mistakes and errors do occur. No warranty is made to the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information provided. The information in the publication may become outdated and there is no obligation to update any such information. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a loss of original capital may occur. Contributors may hold or acquire securities covered in this publication, and may purchase or sell such securities at any time, including security positions that are inconsistent or contrary to positions mentioned in this publication, all without prior notice to any of the subscribers to this publication. Investors should make their own decisions regarding the prospects of any company discussed herein based on such investors’ own review of publicly available information and should not rely on the information contained herein.

There are costs involved that make the realized price lower than the spot price, but we’ll ignore those in our simple model.

A quite similar dynamic led to the collapse in oil prices in the 2010s: high prices, along with new ‘fracking’ techniques led to a massive boom in crude production that wound up crushing the profits of the producers.

Total returns in Newmont are +30%; in Barrick -40%.

For those unfamiliar, ‘WGMI’ is crypto slang for “We [Are] Gonna Make It”, as opposed to ‘NGMI’, or “Not Gonna Make It”.