Fundamentals: The Epic Turnaround At Domino's

DPZ stock is a 100-bagger — which highlights the allure and risk of the turnaround

At the end of 2009, Domino’s Pizza DPZ 0.00%↑ seemed to be in trouble. In three years, the company’s adjusted earnings per share had dropped 44%. Same-store sales in 2009 were up 0.5%, but that followed three straight years of declines.

Unsurprisingly, DPZ stock tanked. And while the financial crisis played a role, the comparison to competitor Papa John’s PZZA 0.00%↑ suggested that Domino’s itself was to blame as well:

source: Koyfin; total return chart from Domino’s initial public offering in 2004 to the end of 2009

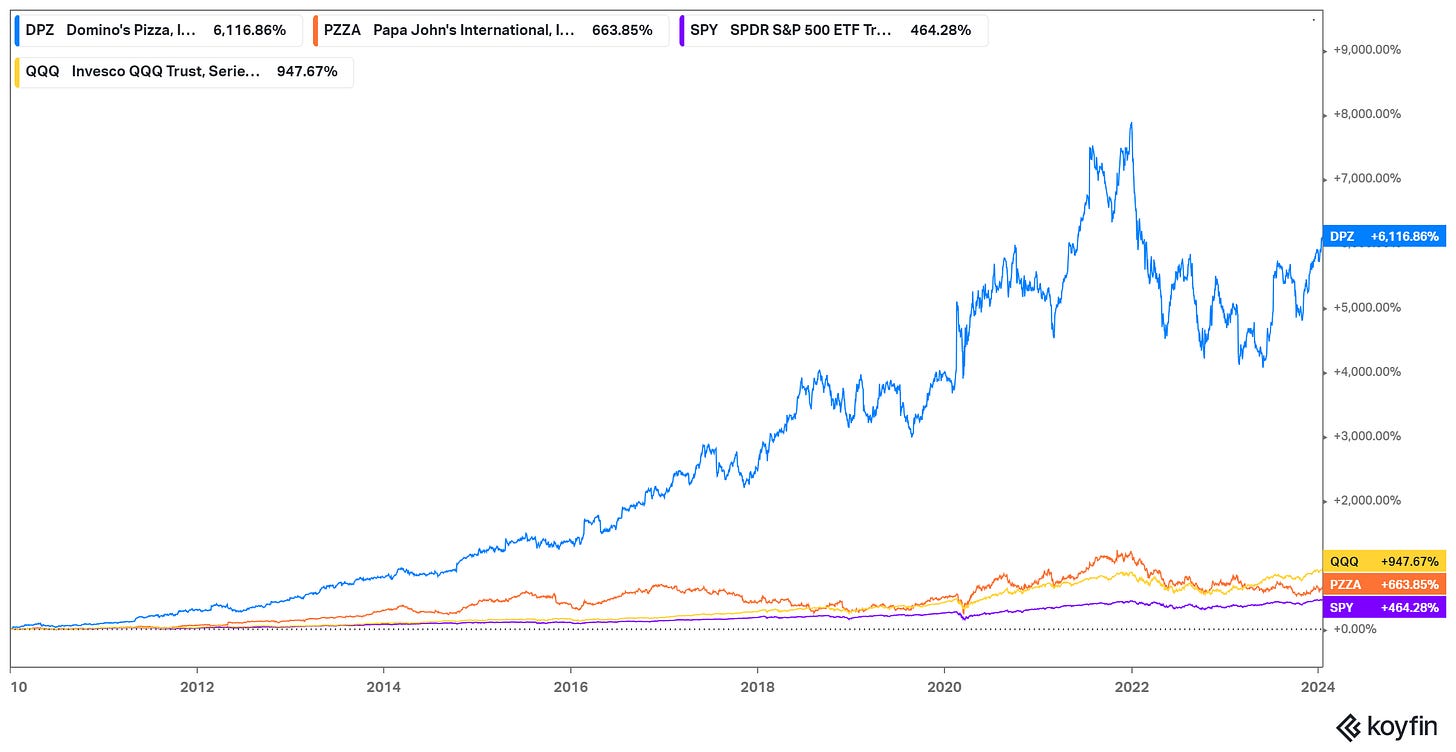

And so on January 5, 2010, chief executive officer David Brandon announced he would step down in March1, to be replaced by Patrick Doyle. What followed was arguably the best turnaround in recent history:

source: Koyfin

There have been a few good ones2. Some investors will choose Apple AAPL 0.00%↑ after co-founder Steve Jobs returned to the company in 19963. But Apple’s problems in the mid-1990s weren’t driven solely by poor execution. The later rise of the company was driven by new products starting with the release of the iPod in 2001. Similarly, Microsoft MSFT 0.00%↑ has been a massive winner since the arrival of CEO Satya Nadella, but that company benefited from the shift to the cloud and the massive installed base that was created under Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer.

Solar inverter manufacturer Enphase Energy ENPH 0.00%↑ incredibly rose more than 100-fold in a matter of years after T.J. Rodgers, the founder of Cypress Semiconductor, joined the board of directors in early 2017. Better operations under Rodgers’s guidance helped, but so did the “green rush” into solar energy.

Where Domino’s stands out is in being such a pure turnaround. An improving macroeconomic picture helped the company, certainly. So did the rise of apps which allowed the company to quickly grow its digital sales. But for the most part, this is a story in which an already well-known stock provided total returns of more than 6,000% in less than 15 years simply through operational improvements.

What Domino’s Did

When Doyle left Domino’s in 2018, it was to much acclaim as the leader of “a remarkable transformation” and “one of the best restaurant CEOs of our time”. But, interestingly, it was under Brandon that Domino’s turnaround actually began.

In 2009, Domino’s changed its pizza recipe. To market the new product, it launched a series of commercials, and a four-minute documentary, that admitted the old product simply wasn’t any good. Doyle himself starred in the documentary, which featured reviews on Twitter and elsewhere complaining, among other things, that the pizza “tastes like cardboard”. In the 4-minute film, Domino’s employees respond to those complaints, and at the end visit a critic with a piping-hot version of the new product.

Doyle added technology development and marketing changes. The chain was one of the first to allow for a saved “easy order” feature on its app. A move to a single point-of-sale program across the entire franchise system allowed for a more advanced digital offering. Per the most recent 10-K, digital sales are about two-thirds of the worldwide total.

This is the archetype of a turnaround case. New (and better) management, a smart strategy, and on-point execution combine to allow the business to finally fulfill its potential. And the Domino’s story highlights what makes the turnaround narrative so tempting: it doesn’t really look that hard.

The rise in DPZ stock has given Doyle a sterling reputation: Burger King owner Restaurant Brands International QSR 0.00%↑ added more than $2 billion in market cap in two days when it named Doyle chairman in November 2022. The irony is that the turnaround began under Brandon, and DPZ had began to rally before Doyle took over. (The stock rose more than 70% in 2009.) Perhaps more importantly, Doyle himself was at Domino’s when the company’s pizza by its own admission “sucked”. Between 2004 and March 2010, Doyle was vice president and then president of the U.S. operations.

No doubt Doyle deserves credit for taking such a drastic step, and it’s certainly possible that it took Doyle (who had previously worked overseas for the company) to convince higher-ups of the wisdom of his strategy. That said, the strategy wasn’t even all that innovative. Privately-held Hardee’s had done the same thing in the early 2000s, launching a line of much-improved burgers and a self-flagellating marketing campaign. Most ads included the tagline: “It's how the last place you'd go for a burger will become the first.”4

So, basically, Domino’s promoted from within and copied someone else’s playbook. Since the end of 2008, total returns in its stock are more than 100,000%. Surely, other companies can do roughly the same thing.

Turnarounds Keep Not Turning

Yet that is not the case. The list of failed turnarounds is far, far longer than the list of successful ones. Rodgers took his Enphase playbook to both battery developer Enovix ENVX 0.00%↑, which continues to struggle in its bid to get to volume production, and solar panel installer Complete Solaria CSLR 0.00%↑, whose very survival is in question. QSR stock has only modestly performed the S&P 500 since Doyle’s hiring, though it has outperformed McDonald’s MCD 0.00%↑ and Wendy’s WEN 0.00%↑.

The relatively low rate of success for turnaround cases perhaps isn’t that surprising, because there are stumbling blocks for both investors and the executives on whom they are betting. The biggest problem in identifying a potential turnaround is identifying whether the downturn in the business is actually a result of execution to begin with.

One obvious example of this problem was in specialty retail during the 2010s. In retrospect, declining sales and profit margins at most retailers during the period were driven by shrinking traffic to traditional shopping malls and the rise of e-commerce. But at the time, both retail CEOs and their shareholders believed that execution was a bigger problem. Better designs, better marketing, lower gas prices, the end of tariffs on Chinese goods were just a few of the potential changes that would offset secular trends and return profits back to prior levels. For many companies in the space, save for the unprecedented explosion in demand during 2020-2021, those profits never got there, or even close.

For executives, the incentives all line up toward creating a narrative of a potential turnaround. Certainly, their egos will benefit: CEOs rarely, if ever, get to top spot without supreme self-confidence. It’s thus nearly impossible for a leader, and particularly the new leader often charged with a turnaround, to admit that there are structural impediments to profit improvement — impediments that he or she simply cannot fix.

A turnaround narrative also gives a new CEO space. This is why the first report under new leadership is so often known as a “kitchen sink quarter”. The company squeezes every piece of bad news it might have — goodwill impairments, layoffs, weak guidance — into a single release. That gives the new CEO time to execute strategic changes, because the implicit message becomes “the last CEO was a dope, it’s going to take some time to clean up this huge mess I was left.”

There’s also the not-insignificant fact that companies themselves are complicated organizations, with conflicting incentives, entrenched leaders at varying levels, bureaucracy, and always-changing competitive threats.

It’s not a coincidence that some of the most disappointing supposed turnarounds this century have been companies that were leaders last century: General Electric GE 0.00%↑, IBM IBM 0.00%↑, Kraft Heinz KHC 0.00%↑. Larry Culp looked like one of the greatest CEOs of all time when he was at Danaher DHR 0.00%↑, to the point that during his tenure Danaher produced other great CEOs. Despite no shortage of activity, he’s appeared relatively pedestrian at GE.

What To Do About The Uncertainty Of Turnarounds

The core issue with turnarounds is that no one really knows, certainly at first. A CEO who has been with a company for six weeks or six months is still learning the lay of the land. Investors may not be able to decipher whether the core problem is execution, or competition, or secular changes in the customer base. In nearly all cases, each of those factors is playing a role, but the relative proportion will always be unclear.

And of course, those factors are hardly independent. Domino’s could have rolled out its turnaround strategy in 2012, instead of 2009. And by that point it’s possible the company’s reputation would have been damaged to the point that a turnaround became impossible, and/or the company’s best managers had departed for more successful chains.

All told, it’s much easier to forecast a business that is performing well than it is one performing poorly. Domino’s could have made a ‘better’ pizza that wasn’t as good, blown its one chance at restoring its reputation, and spent another decade as a perpetually disappointing turnaround. Meanwhile, in 2016, Microsoft’s adjusted earnings per share hadn’t moved for four years5. Many investors at the time thought it would be the “next IBM”, doomed to see its empire carved up by smaller, younger, more nimble rivals.

To be sure, the incredible returns in DPZ, and solid returns in other turnarounds, show the strategy shouldn’t be dismissed out of hand. But the history of turnaround cases does provide some lessons for investors.

The first is simple: be skeptical. Nearly all struggling companies are going to offer some version of a turnaround plan, whether under existing management or new leadership. They will work on paper, because, again, they always work on paper. In practice, they’re likely to fail, and there is an argument that, owing to rapid technological change, they’re now more likely to fail.

The second is that turnaround strategies need to be specific in both the problems being diagnosed and the solutions being offered. Domino’s is a perfect example: our pizza is not good enough, we’re going to fix it, we’re going to tell people that we fixed it. In contrast, most 2010s retailers offered vague assertions of ‘better’ merchandise or improved marketing. Fading old-line giants like IBM and Kraft Heinz have made acquisitions and shed businesses to ostensibly improve reported revenue and profit growth. But beyond financial engineering have often failed to deliver coherent, measurable plans to create better businesses.

The third is again highlighted by Domino’s: there’s no rush. The new pizza and the new ad campaign in fact was a relatively quick hit. In the first quarter of 2010, domestic same-store sales increased 14%. And on the earnings call, Doyle talked up multiple metrics in terms of existing and recaptured customers that further supported the idea that the turnaround had a solid foundation. (Amazingly, DPZ stock actually declined 13% in trading that day.)

At that point, Domino’s had tripled since the end of 2008, so investors had missed out on some gains by not perfectly timing the bottom. But there was still plenty more upside ahead: DPZ provided total returns of 3,615% since the Q1 2010 release.

Of course, not every turnaround will prove to be one of the best stocks of an entire decade. And that’s exactly the point: most are going to whiff. But in many cases, the turnaround opportunity still implies three-digit upside. If, for instance, a stock is down 60% from its high, a return to past earnings and past valuation suggests returns of 150%.

The size of those returns is part of what makes turnaround cases so tempting, and why investors are willing to take on the risk that the turnaround doesn’t work. The history of successes like Domino’s and Enphase, and the long list of failures, shows that it’s probably wise to minimize that risk. After all, the rewards can still be more than attractive enough.

As of this writing, Vince Martin has no positions in any securities mentioned.

Disclaimer: The information in this newsletter is not and should not be construed as investment advice. Overlooked Alpha is for information, entertainment purposes only. Contributors are not registered financial advisors and do not purport to tell or recommend which securities customers should buy or sell for themselves. We strive to provide accurate analysis but mistakes and errors do occur. No warranty is made to the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information provided. The information in the publication may become outdated and there is no obligation to update any such information. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a loss of original capital may occur. Contributors may hold or acquire securities covered in this publication, and may purchase or sell such securities at any time, including security positions that are inconsistent or contrary to positions mentioned in this publication, all without prior notice to any of the subscribers to this publication. Investors should make their own decisions regarding the prospects of any company discussed herein based on such investors’ own review of publicly available information and should not rely on the information contained herein.

Brandon became the athletic director at the University of Michigan; there, too, he resigned under apparent pressure, in 2014.

I received some good suggestions on Twitter this week.

We discussed 1990s Apple in this space just last week.

For readers unfamiliar with that chain, its burgers in the early 2000s were as bad as Domino’s pizza toward the end of that same decade.

Adjusted EPS was $2.79 in fiscal 2016, and $2.73 in fiscal 2012.

Great post--thanks guys!