Fundamentals: Bausch's Terrible Balance Sheet

We continue our series on debt by working through one of the public market's most indebted companies

In our last two articles in this series, we’ve looked at debt, and what it means for equity investors. In this article we’ll show how debt can make a seemingly cheap stock, outrageously expensive.

We closed our last piece by highlighting Bausch Health, which by one metric looks like perhaps the cheapest in the entire market.

Based on consensus estimates, BHC trades at 2.44x fiscal 2024 earnings per share. And that’s with the company growing EPS 13.7% in 2023 and another 12%-plus expected in 2024.

Given double-digit growth, a sub-2.5x multiple seems ludicrous. Indeed, an investor could argue — and we’ve heard versions of this claim in the past — that Bausch is a no-lose proposition. After all, in less than three years, the company is going to post earnings that will likely be greater than its current market capitalization.

Of course, the equity market doesn’t just leave no-lose propositions lying around. And even a casual look at BHC trading volumes suggest this isn’t a stock the market is ignoring.

So the question is why BHC looks so cheap — and if, indeed, it is so cheap. A big part of the answer comes down to the balance sheet, which makes Bausch a perfect model for a step-by-step primer on understanding debt as a part of equity research.

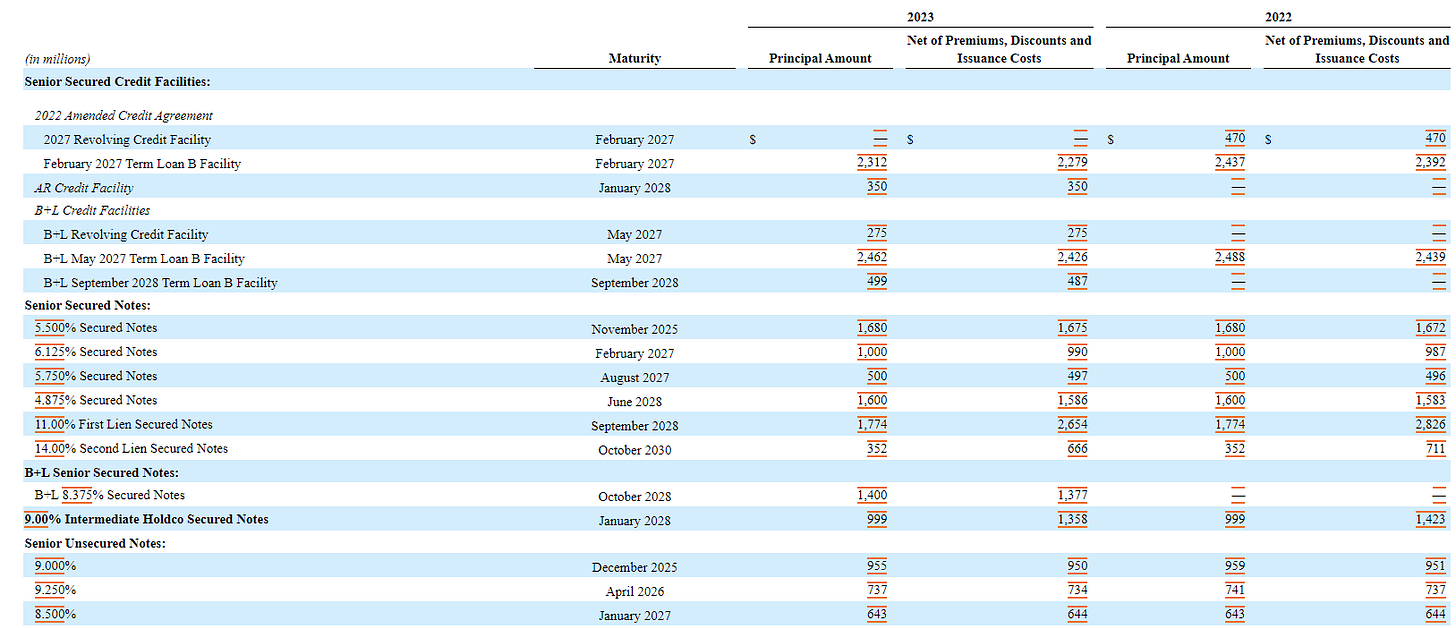

source: Bausch Health 10-K, p. F-41

A Look At Bausch Health

In 2010, a pair of drugmakers, Biovail and Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, merged in a $3.2 billion deal. The deal technically merged Valeant into Biovail, a Canadian concern which marketed antidepressant Wellbutrin and other drugs. But the combined company retained the name of Valeant, which had developed antiviral ribavarin and, via acquisitions, built out a fast-growing business in dermatology.

The ‘new’ Valeant was led by the chief executive officer of the ‘old’ Valeant, Michael Pearson. Pearson had executed 15 acquisitions in three years when the merger was announced; his strategy remained the same in his new role. If anything, it ramped up. In 2011, the company made eight acquisitions of companies or product rights with total upfront payments of $2.7 billion; many of the agreements had milestone payments and/or royalties on future sales as well. The following year, nine deals totaled more than $3.5 billion.

In 2013, Valeant paid $8.6 billion for Bausch + Lomb BLCO 0.00%↑ (it would spin off a portion of its ownership in 2022). The next year, it tried and failed to buy Allergan1. Undeterred, Valeant spent $15 billion on gastrointestinal drugmaker Salix in 2015.

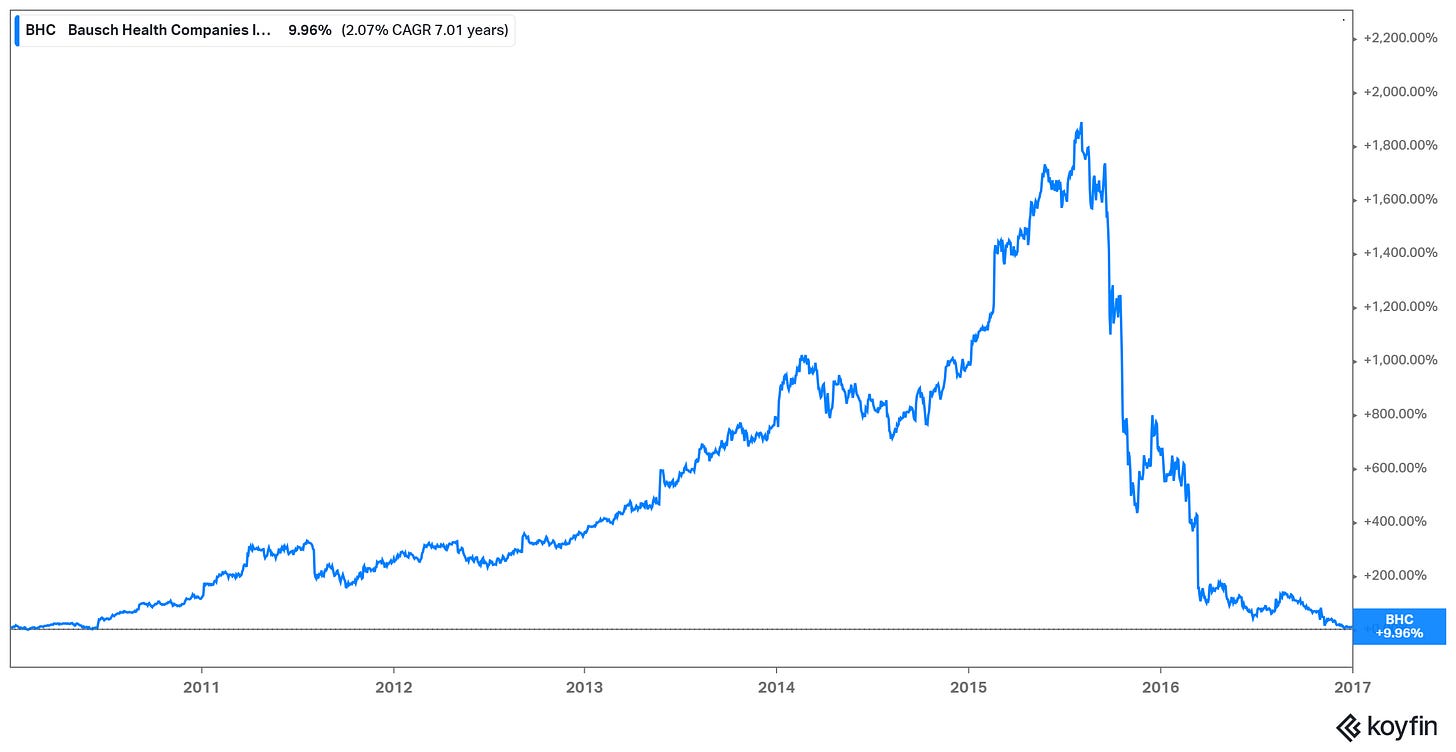

The strategy was incredibly successful — until it wasn’t:

source: Koyfin. Chart from 1/1/10 to 1/1/17

It was short sellers who helped catalyze the plunge in Valeant stock. Andrew Left of Citron Research, following work done by independent journalists, accused the company of “Enron-like accounting” in its use of a specialty pharmacy.

Regulators caught on, with some help from Valeant itself: reportedly, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission started its investigation of Valeant after the company asked the SEC to investigate its critics. The same acquisition strategy that had driven Valeant stock up added to the pressure, particularly after Pearson admitted the company had been too aggressive in raising prices of acquired drugs.

By 2016, Pearson was gone. In 2018, the company changed its now-toxic name to Bausch Health. But an important legacy was left: a massive amount of debt on the balance sheet, used to pay for the acquisitions under Pearson’s watch.

Why Is BHC So Cheap?

In the stock market, when something seems so ridiculously cheap, there’s usually a good reason why. At 2.5x earnings with double-digit growth, BHC certainly qualifies as “ridiculously cheap”.

And so an investor’s first question with a stock like this is: why does such an opportunity seem to exist? In other words: what’s the catch?

With Bausch, there are two. The first is that it is a pharmaceutical company, and those can’t be valued like any other businesses. Early-stage pharmaceutical stocks are valued based on the potential of their drugs in development. More mature companies face what is known as a “patent cliff”. As the patents for key drugs expire, generic competitors flood in, and revenues can, as the name suggests, fall off a cliff. And so the company must successfully — and continually — launch new products to keep overall revenue stable, let alone growing.

For a generalist investor, trying to model the puts and takes of a diversified drug portfolio is essentially impossible. There are constant legal challenges to existing patents (Bausch is dealing with a legal dispute over Xifaxan, which drove ~20% of sales last year), pharmacological questions about the potential success of new drugs and competitive products, marketing and market size considerations, and many more complications.

But one of the points we’ve made in this series generally is that common sense can go a long way. The fact that BHC is trading at less than three times earnings pretty much by definition means the market sees those earnings as heading into a period of decline. That decline doesn’t necessarily begin in 2024 — neither management nor Wall Street believes as much — but the market is telling us it will begin soon.

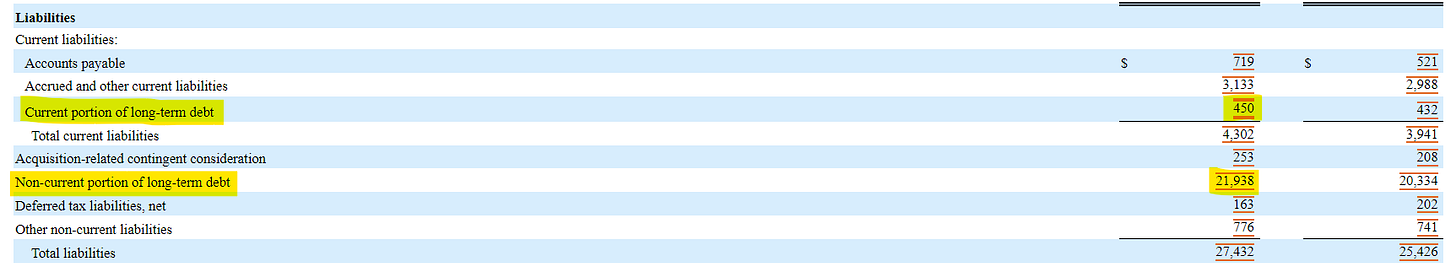

The other factor here is debt. As we noted in our piece on financial leverage last year, debt lowers the price-to-earnings multiple of a stock. And Bausch has a lot of debt, as even a cursory look shows:

source: Bausch Health 10-K (author highlighting)

Again, common sense is helpful here. Bausch has a market capitalization of $3.5 billion. It has debt of $22.4 billion (and just under $1 billion in cash).

To some degree, then, we’ve already answered the key question. Why is Bausch so cheap? It’s a hugely leveraged (net debt is six times its market capitalization) pharmaceutical business with serious risk of a decline in profits. In that context, the 2.4x P/E multiple isn’t a sign of a market gone mad. Instead, it actually seems somewhat logical.

Bankruptcy Odds

The question, of course, is how logical. Common sense says BHC is a risky play. But in turn that also suggests it’s a potentially lucrative play as well. To oversimplify the story here, BHC trades at 7.6x EV/EBITDA, with net debt at about 6.6x EV/EBITDA. Expand that multiple one turn to 8.6x, and the stock roughly doubles. That’s, again, an oversimplified, on-paper model focusing on one metric, but it gets to the idea that there is potential for BHC to post huge gains if the worst-case scenario is avoided.

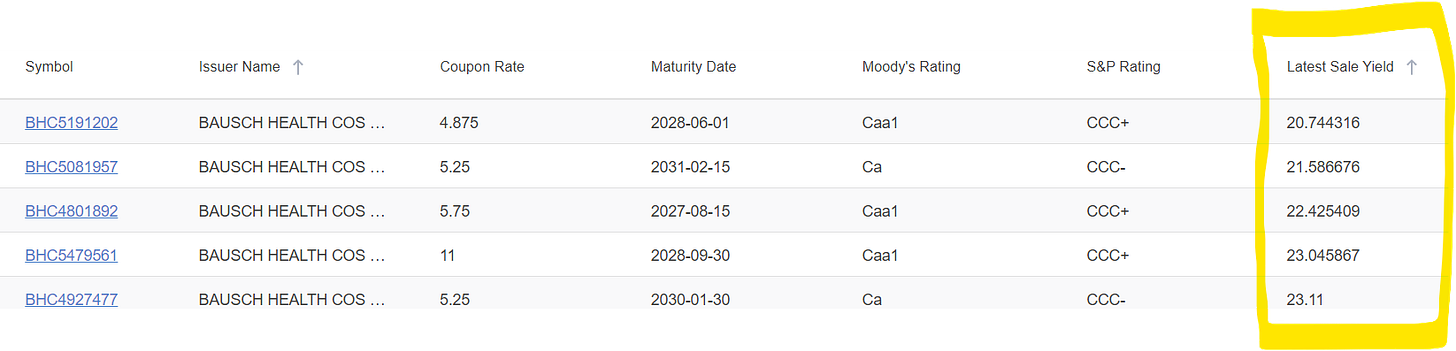

And as we noted last time, one way to judge the likelihood of that worst-case scenario is to look to the credit markets. That is the job of a debt investor: to accurately price the odds of the worst-case scenario. Those investors are pricing in pretty high odds of disaster here:

source: Finra (author highlighting)

What’s notable is the fact that near-dated maturities have high yields. One of the bonds not shown, a 6.125% issue that matures in February of 2027, has a yield to maturity of 24%.

We know, via common sense, that those yields suggest the bond market is pricing in a material chance of a restructuring. How material is up for debate. Calculating bankruptcy odds via a bond price would look something like this:

risk-free return = [bankruptcy odds]*[returns in a restructuring] + [1-(bankruptcy odds)]*[returns if the debt is repaid]

In other words, it’s an expected value calculation, with two possibilities: bankruptcy before maturity and no bankruptcy before maturity.

We know the return if there is no bankruptcy. The catch is that we don’t know the return in a restructuring. Does Bausch start skipping interest payments later this year, or in 2026? Is there any recovery value for these bonds?

We do know from the 10-K (p. 66) that in 2022 Bausch exchanged about $5.6 billion in unsecured debt for new secured debt with a face value of roughly $3.1 billion. And that unsecured debt had interest rates ranging from 9% up to 14% — the latter a rate that still implies a pretty high chance of bankruptcy. And those bonds are in front of the unsecured issues in any bankruptcy scenario.

Recovery value for these bonds may well be zero, or close. Based on that assumption, we can get an estimate of bankruptcy odds priced in by the bond market (we’ll put the math in a footnote2): at least 40% by 2027.

The Claim On Cash Flow

It bears repeating: investors don’t have to run this math every time. If a press release cites a 1.8x leverage ratio, and a decently-growing stock trades at, say, 23 times earnings, the exact details of the balance sheet are probably relatively immaterial. It’s always worth checking, but simply reading the 10-K (particularly with experience) will almost always surface any potential issues.

Even for a name like Bausch, investors don’t necessarily have to do this kind of math at all. Algebra isn’t required to prove the core point: when yields start getting to the mid-teens, the odds of a bankruptcy start becoming significant. And a bankruptcy almost always means shareholders get wiped out3.

There’s another important structural point to consider. Simply dodging a bankruptcy in 2027 doesn’t mean BHC is a buy. The stock may rise between now and then as it’s de-risked. But from a fundamental perspective, that alone doesn’t get the job done.

In theory, a stock price should be equal to the sum of its discounted cash flows in the future (i.e., a dollar in cash flow generated in 2033 is worth much less than one today). In essence, investing is about trying to find situations where that cumulative total is much higher than the current stock price suggests.

But for heavily indebted companies like Bausch, it’s bondholders that have claim on the cash flow first and foremost. As the 10-K notes, under the terms of the credit facility and senior bonds, Bausch can’t distribute any cash flow to shareholders.

It’s not quite right to say that Bausch has to repay all of its debt before its stock is worth anything at all. But it’s somewhat close. The next billions of dollars in Bausch’s free cash flow are going to bondholders. Only if there’s enough left over will stockholders see a dime. And so the argument that BHC is a steal because it can earn its market capitalization in less than three years falls completely flat: it might earn that cash, but shareholders won’t get that cash.

Admittedly, few companies are in a financial position quite like this. But many are restricted from paying dividends or doing share repurchases until the debt is repaid or at least reduced to a more manageable level.

The Bausch + Lomb Spin-Off

We’ll close with an admission. In the interest of using BHC as a primer for understanding debt mechanics, we left out a key and quite interesting part of the story.

As noted above, Bausch Health spun out part of its stake in Bausch + Lomb in 2022. It still owns 88% of that business; it long has planned to distribute that ownership to shareholders in the second step of the spin off.

Bausch + Lomb has a market cap of $5.6 billion. The Bausch Health stake is thus worth, at least on paper, about $4.9 billion. And so if Bausch Health could fully spin off that stake to BHC shareholders, that alone would represent 40% upside to the current BHC stock price.

Unfortunately, those efforts have been paused. Incredibly, the issue is a lawsuit not from Bausch Health bondholders, but from its former shareholders, who hold a multi-billion dollar judgment against the company for its past activities. And so this aspect of BHC stock, like the headline valuation, provides more evidence for perhaps the most important investing lesson: if something looks too good to be true, it probably is.

As of this writing, Vince Martin has no positions in any securities mentioned.

Disclaimer: The information in this newsletter is not and should not be construed as investment advice. Overlooked Alpha is for information, entertainment purposes only. Contributors are not registered financial advisors and do not purport to tell or recommend which securities customers should buy or sell for themselves. We strive to provide accurate analysis but mistakes and errors do occur. No warranty is made to the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information provided. The information in the publication may become outdated and there is no obligation to update any such information. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a loss of original capital may occur. Contributors may hold or acquire securities covered in this publication, and may purchase or sell such securities at any time, including security positions that are inconsistent or contrary to positions mentioned in this publication, all without prior notice to any of the subscribers to this publication. Investors should make their own decisions regarding the prospects of any company discussed herein based on such investors’ own review of publicly available information and should not rely on the information contained herein.

Actavis won the bidding war, and that company eventually was bought by AbbVie ABBV 0.00%↑.

6.125% 2027s are currently priced at 64; a $1,000 face value bond costs $640. For that, investors receive $183.75 in interest (three years at $61.25 per year; the interest rate of the bond is based on face value) plus $1,000 in principal repayment. If repaid, our ending balance is $1,183.75.

If the bond never pays interest — ie, Bausch skips the interest payment — returns are zero. That does seem unlikely; given 2024 expectations, bondholders probably get at least two interest payments, leading to ending cash of $61.25.

$640 invested in a 3-year Treasury bond at the current yield would leave an ending balance of $729.

our algebra would look this then, with bankruptcy odds ‘b’:

61.25*b + 1183.75*(1-b) = $729.

Solve for b and you get just over 40%. Bear in mind that a recovery value above zero and/or additional interest payments actually mean the implied odds of a bankruptcy are higher than 40%. So does the fact that the buyers of distressed bonds aren’t necessarily trying to price to the risk-free rate, but rather something higher. The math can be much complicated (and is for credit investors) but hopefully this gives some color as to how significant the odds of a restructuring are.

As we noted last week, two well-known recent exceptions are General Growth Properties in 2010 and Hertz HTZ 0.00%↑ in 2021. But there are literally thousands of examples over that period where the rule held.

The math here is really interesting to me as a noob. Thank you so much for including it in the footnotes. I wanted to ask if you have read "Dear Mr. Buffett" by Janet Tavakoli and specifically the chapter on how Berkshire insures baskets of junk bonds? You talking about recovery value made me think of this chapter. Thanks again.