Fundamentals: Understanding Book Value

Reviewing an unusual metric that is often meaningless, yet sometimes important

Book value, also known as shareholders’ equity, is an odd concept because quite often, it doesn’t matter at all.

One of the themes we’ve hit on multiple times in this series is the idea that accounting is as much an art as a science, as we discussed in our comparison of earnings and cash flow. Similar to earnings, book value is not necessarily a perfect representation of what it tries to represent: the actual value of a company’s assets, less its liabilities.

The catch, however, is that valuing a company’s assets is exceptionally difficult. Indeed, the stock market itself is an argument over the ‘true’ value of a company’s assets (net of debt, of course). And the structure created by accounting practices is poorly suited for the heavily intangible assets owned by so many modern companies.

So, for many stocks, book value is basically a useless metric. But what makes book value interesting is that, for some stocks, it’s exceptionally important.

What Is Book Value?

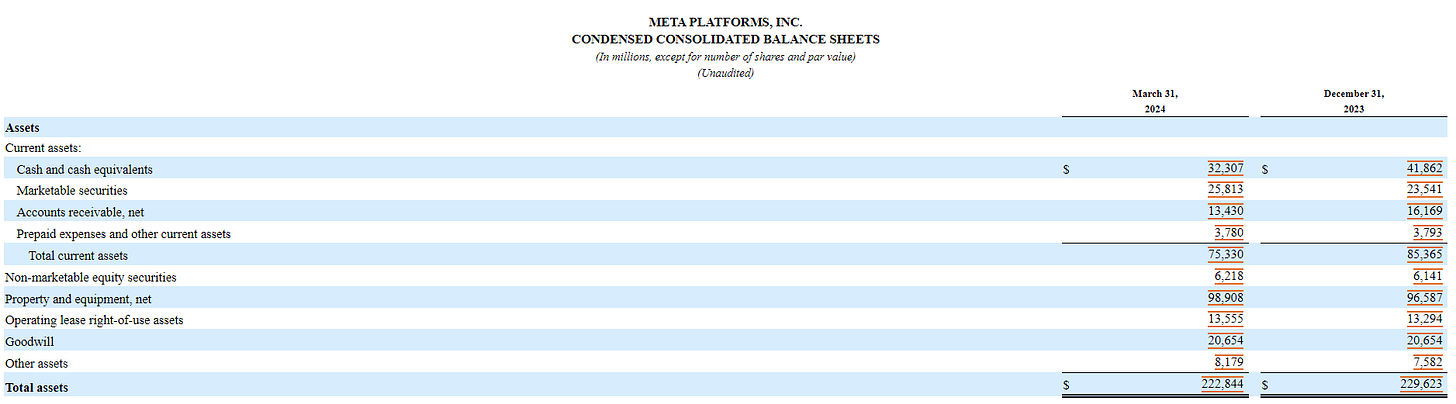

On a balance sheet, shareholders’ equity, or book value, is calculated in two ways. First, the company nets out its liabilities against its assets. But shareholders’ equity also needs to equal the sum of additional paid-in capital (representing sales and issuance of stock above par value), accumulated other comprehensive income or loss (from items such as equity investments), and retained earnings (the sum of profits in the company’s existence). We can see the line items in a recent quarterly filing from Meta Platforms META 0.00%↑, formerly known as Facebook:

source: Meta Platforms 10-Q, first quarter 2024

The second calculation usually is of little interest to investors. Retained earnings can occasionally be interesting in showing a company’s history. For instance, Plug Power PLUG 0.00%↑, founded back in 1997, has an accumulated deficit (the mirror image of retained earnings) of nearly $4.5 billion. Its market cap is just $1.6 billion; those two figures give an idea of just how much capital Plug Power has spent in its 27-year history.

Its the first calculation — assets versus liabilities — that has some relevance to an investment case. But, as Meta shows, book value has some significant limitations.

Meta And The Problem With Book Value

For the most part, a company’s liabilities aren’t subject to significant accounting effects. There are some required calculations around line items like contingent consideration (potential payouts to the former owners of acquired businesses) or long-term tax liabilities, but those calculations have reasonable constraints. Generally speaking, both the company and the investors know what total liabilities are to a reasonable degree of certainty (debt, for instance, has a fixed principal amount).

But for assets, it gets a little trickier, because with modern companies, something is missing:

source: Meta Platforms 10-Q, first quarter 2024

Meta Platforms has book value of $149 billion. Current accounting rules suggest that is the value of the company’s equity. However, the actual market in which META stock trades applies an extremely different valuation: Meta has a market capitalization of $1.1 trillion, more than seven times its book value.

Many of Meta’s assets are common and easy to value: cash, marketable securities, and accounts receivable are all known figures. Property and equipment gets a little more dicey. Meta buys servers and depreciates them on a four- to five-year lifespan; buildings are depreciated over 25 to 30 years. Here, we already see a bit of an issue to which we will return later: buildings aren’t necessarily depreciating assets.

But the broad point still holds: many of the assets in the property and equipment line item degrade over time, and that expense is imperfectly calculated through the depreciation of those assets, almost always on a straight-line basis. In other words, ~20% of the server cost is charged as depreciation each year, an expense accounted for in the profit and loss statement.

Goodwill is a somewhat nebulous figure. It is an intangible asset that represents the premium paid in acquisitions; the purchase price, less the net “fair value” of the assets, is booked as goodwill. But, like other intangible assets, goodwill can’t be increased — it can only be decreased through an impairment.

Famously, Meta (then Facebook) paid $1 billion for Instagram in 2012. The company booked just $433 million in goodwill related to the acquisition. Again, the figure can’t go up, even though Instagram now is a key part of a business worth over $1 trillion.

What is even more problematic is that there is no line item for Meta’s own intangible assets. The servers that power Facebook are represented; the money due from advertisers is on the balance sheet. But the Facebook brand, its network, its user base, its power are, by accounting standards, not considered assets.

This seems bizarre. But those accounting standards mean that book value is essentially useless when dealing with companies whose businesses run on intangible, rather than tangible assets. In the modern world, this means software companies, fabless semiconductor developers, social media companies, and even retailers.

Indeed, META is not an outlier. The six most valuable companies on U.S. exchanges all have market capitalizations that are at least seven times their book value. The price-to-book for Nvidia NVDA 0.00%↑ is more than 50x; Apple AAPL 0.00%↑ 36x; Microsoft MSFT 0.00%↑ nearly 12x. Those multiples are not only high, but given the treatment of the intangible assets which power those hugely profitable businesses, those multiples are simply meaningless.

When Book Value Matters

And yet:

To recap Berkshire’s own repurchase policy: I am authorized to buy large amounts of Berkshire shares at 120% or less of book value because our Board has concluded that purchases at that level clearly bring an instant and material benefit to continuing shareholders.

Perhaps the greatest investor ever, Warren Buffett, happily used book value as a metric for repurchasing his own company’s shares, as detailed in the quote above from the company’s 2016 shareholder letter1.

Given the limitations of book value, that policy seems surprising. But the reason Berkshire based its repurchases on book value is because, at the time, many of the company’s assets were properly valued. Berkshire’s book value of $620 billion included goodwill and other intangible assets (booked via acquisitions) of about $100 billion. A good chunk of the assets, however, were cash and equity investments (representing Berkshire’s massive portfolio) which were fairly valued by accounting rules.

Berkshire’s policy highlights the kind of business for which book value can be useful: one in which accounting rules require that assets be valued at, or close, to their fair market value. One obvious sector where book value matters is financials (which, to some extent, Berkshire belonged in 2016). Major banks are often valued in part on price-to-book — and that makes some sense. The assets of a bank, in particular, are relatively fixed, as seen in the JPMorgan Chase JPM 0.00%↑ balance sheet:

source: JPMorgan Chase 10-K, 2023

Of course, the same is true of liabilities:

source: JPMorgan Chase 10-K, 2023

And so an investor can use book value — and particularly tangible book value, which excludes intangible assets and goodwill — as a reasonable guide to what the bank’s actual net assets are.

Using P/B In Financials And Other Sectors

To be sure, this isn’t perfect: as we learned during the regional banking crisis last year, following the failure of Silicon Valley Bank, some assets aren’t necessarily marked to market. And there are accounting maneuvers banks can use to impact their book value (such as classifying securities as “hold to maturity”).

Still, from a rough standpoint price to book represents the market’s view on the strength of the underlying financial franchise. A good bank should get a premium on its book value, since the bank presumably can drive consistent, solid returns on its equity and assets. A more questionable bank, not so much. And so P/B winds up being, at worst, a reasonable proxy for the market’s view of various financial franchises, particularly major banks:

source: Koyfin

In this vein, P/B can be used in terms of relative valuation, even as a broad starting point for thinking through an investment. Clearly, the market places a premium on JPM, while Citigroup C 0.00%↑ remains a turnaround story (as it’s been for years). As for European banks UBS UBS 0.00%↑, Barclays BCS 0.00%↑, and particularly Deutsche Bank DB 0.00%↑, investors clearly have concerns:

source: Koyfin

So a qualitative bull case for these banks can absolutely be based on relative P/B or P/TBV multiples. If Deutsche Bank can get its act together, and see its business valued even at the net value of its assets, the stock (in theory) can rise at least 150% as P/TBV moves toward 1x2.

Similarly, the multiple scandals at Wells Fargo WFC 0.00%↑ have led investors to apply a discount relative to JPM and Bank of America BAC 0.00%↑. But the discount could narrow if the bank satisfies regulators and returns to normal (hopefully ethical) operations.

To be sure, banking stocks require significant, and often idiosyncratic, analysis. But book value and tangible book value can be part of that analysis, and the same is true for similar sectors where assets are both important and properly measured by accounting rules. That includes other financial industries like insurance or brokerages3, and homebuilders.

When accounting rules create a reasonable picture of a company’s actual net asset value, then price to book does have some value. And the gap between market cap and book value and/or tangible book value becomes a reflection of investors’ view of the actual operating business.

The Limitations Of Book Value

Put another way, the gap between market cap and book value, when book value is reasonably accurate, is the market’s valuation of what accounting rules can’t and don’t measure.

But, again, sometimes book value isn’t accurate. In 2018, Berkshire Hathaway abandoned its decades-long focus on book value. Buffett wrote that “the annual change in Berkshire’s book value…is a metric that has lost the relevance it once had.” A key problem was the company’s shift toward acquiring businesses in full instead of equity investments.

As Buffett noted, “accounting rules require our collection of operating companies [emphasis in original] to be included in book value at an amount far below their current value, a mismark that has grown in recent years.” Berkshire’s balance sheet could reflect the success of its investments, which were marked to market, but it could not and can not reflect the success of its acquisitions.

That distinction highlights the limitations of book value. It also gets to a somewhat odd truism: the better the business, the less book value matters. The best businesses have attributes — the wisdom of magnificent investors, a massive technological edge, network effects of dominant social media platforms — that accounting rules can’t measure. But, of course, it’s precisely those attributes that create world-changing companies. Book value can to some extent value a company’s assets, but it can’t really capture what those companies are able to do with them.

As of this writing, Vince Martin has no positions in any securities mentioned.

Disclaimer: The information in this newsletter is not and should not be construed as investment advice. Overlooked Alpha is for information, entertainment purposes only. Contributors are not registered financial advisors and do not purport to tell or recommend which securities customers should buy or sell for themselves. We strive to provide accurate analysis but mistakes and errors do occur. No warranty is made to the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information provided. The information in the publication may become outdated and there is no obligation to update any such information. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a loss of original capital may occur. Contributors may hold or acquire securities covered in this publication, and may purchase or sell such securities at any time, including security positions that are inconsistent or contrary to positions mentioned in this publication, all without prior notice to any of the subscribers to this publication. Investors should make their own decisions regarding the prospects of any company discussed herein based on such investors’ own review of publicly available information and should not rely on the information contained herein.

You can view all of Berkshire’s letters since 1977 at the company’s exceptionally bare-bones website.

Deutsche actually is executing on its turnaround somewhat; the stock is up more than 50% since October.

For instance, price to book was a pillar of our successful bull case for Robinhood HOOD 0.00%↑ last year.

It's probably also worth mentioning the effect of buybacks on book value.