Fundamentals: A Deep Dive On Stock-Based Compensation

What SBC means, and what Tesla teaches us

The core reason stock-based compensation (the issuance of stock, either as grants or options, to employees) exists is to align incentives. It might seem like shareholders, executives and workers have broadly the same goal: to grow the business. But that’s not necessarily the case.

In fact, there’s a classic principal/agent problem in the structure of a corporation. Managers and workers are the agents running the business on behalf of the principals, the equity investors who actually own the business. And those equity investors want their companies to take risks.

Certainly, that should mean intelligent risks. Shareholders won’t cheer if a CEO uses corporate cash to, say, build a search engine or create a new division from scratch that serves an entirely different industry. But to some degree, equity investors want some risk. That’s why they own equity, and not lower-risk debt, in the first place.

But for executives who are paid purely in cash, there isn’t a direct incentive to take risk. To some degree, the incentives point the other way. “Good enough” becomes more than good enough. A CEO’s best bet is to not rock the boat, and importantly not to take risk. Risk increases the potential for downside, which increases the possibility of getting fired and losing the cushy cash salary. Yet the upside potential added by risk creates little direct financial gain for the executive.

In this model, a CEO’s financial incentives are actually much closer to that of a bondholder, rather than a stockholder. She simply wants the company to be stable, so she can keep getting paid. Any upside in equity value is someone else’s concern.

For employees, the use of equity-based compensation is more straightforward. It gives those employees a stake in the business and, presumably, extra motivation. For early-stage startups, stock-based comp is perhaps the only way to attract high-value talent. Cash-only compensation eats up too much capital or leaves the company hiring only those employees unwanted by larger firms.

This is the theory, anyway. In practice, there are real concerns — and real questions.

The Rise Of Stock-Based Compensation

Over the past couple of decades, the use of stock-based compensation has risen dramatically, as detailed in this excellent paper from Morgan Stanley:

source: Morgan Stanley, “Stock-Based Compensation: Unpacking the Issues”

To be sure, this trend doesn’t solely reflect changing preferences by corporate boards of directors (who ultimately make the decisions regarding stock-based compensation). As Morgan Stanley notes, companies in the Russell 3000 today are younger (owing to the tech boom of the past three decades). Younger companies are more likely to use stock-based comp:

source: Morgan Stanley, “Stock-Based Compensation: Unpacking the Issues”

But it’s worth noting that the rise in stock-based compensation has had a more significant impact than the above two charts might suggest. A 2021 paper calculated that the average operating margin for the Russell 3000 as a whole is in the range of 11%. Notably, that figure is based on forward-looking estimates from analysts. Given that they aim to track the adjusted numbers provided by most companies, those estimates usually exclude stock-based compensation.

As a result, some investors argue that a material proportion — more than 10% — of the operating profits of U.S. public companies are not real. They exist only because the companies are paying more and more of their executives and employees in more and more stock. Yet, skeptics claim, investors and analysts are choosing to ignore that fact.

What Does Stock-Based Compensation Cost?

Companies are required to disclose the amount of their annual stock-based compensation. This creates some difficulty, because it’s not clear what exactly that amount should be.

There are all sorts of differing awards. Restricted stock — simply a grant of shares in the company — can vest over time: an employee gets 100,000 shares of stock, and each year 25,000 of those shares become unrestricted (and thus can be sold). Performance stock, as the name suggests, vests based on performance, and boards can and do choose from all sorts of metrics: total shareholder return, operating margins, even the results of a key business unit1.

Stock options, meanwhile, provide the ability to buy shares at the exercise price — but they, too, take myriad forms. Many vest over time; some have an exercise price linked to market conditions (for instance, the stock outperforming peers). The exercise price can be equal to, above, or below the current market price, for varying reasons.

All of these various compensation instruments receive differing accounting treatments in an effort to create a best approximation of their actual cost at the time. For instance, restricted stock is usually calculated at the cost of the total award at the grant date (ie, 1,000 shares at $50 is an expense of $50,000), with the cost then recognized over the vesting period. Stock options are accounted for using the Black-Scholes method2.

But one of the problems in terms of forward-looking guidance from companies is that a key input for many of these calculations is the stock price itself. In other words, a company knows that it will issue restricted stock and/or options over the course of the year, but it doesn’t actually know what that issuance will cost.

And so companies that use stock-based compensation in size often will guide to adjusted figures. This is not, as skeptics claim, because the company is trying to ‘trick’ investors (or at least, that’s not the sole reason). It’s because the actual accounting expense of stock-based compensation can be volatile, and likely will be more volatile based on the underlying stock price. Of course, the heaviest issuers of stock-based compensation are younger and smaller companies — precisely the kind of companies that usually have the most volatility in their stock prices.

The reliance on the stock price in calculating expense in and of itself is a tell that the accounting for stock-based compensation, like other forms of accounting, is not gospel. There are assumptions baked in, and factors that mean the line for both stock-based compensation in the earnings and cash flow statements may not be telling the entire story.

The Musk Awards

The two major awards granted to Tesla TSLA 0.00%↑ CEO Elon Musk give a sense of how these packages can work, how complex they can be, and what the SBC line item might actually mean.

In 2012, Tesla gave Musk his first package. It seemed huge at the time. Musk received options to buy 5% of Tesla at the stock price at the time the package was awarded ($31.17 per share, or $2.08 adjusted for subsequent stock splits). But for all of those options to vest, Tesla had to reach ten operational milestones, and had to hit ten successive levels of market capitalization. At the highest end, Musk’s package would be worth roughly $2 billion — but it would require Tesla’s market cap to rise by more than 13x3 and for the business to take the following steps:

source: Tesla proxy statement, 2013

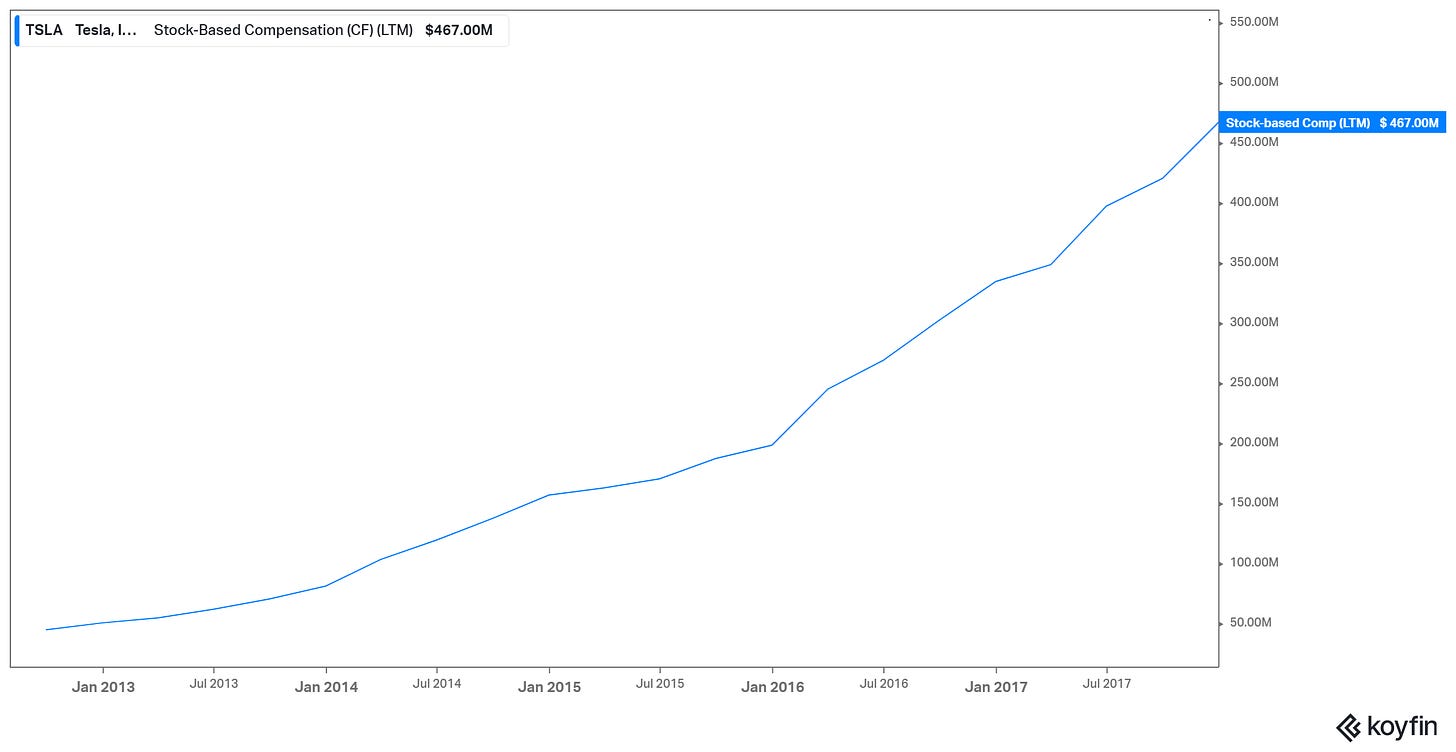

As it turned out, Tesla kept hitting its goals. And so the company booked ever-high stock-based compensation to Musk, both to account for the vesting of options granted in 2012, as well as the higher probability that future tranches would vest as well. The growth of the business (and the workforce) increased SBC as well, but reading through 10-K filings from the time, the Musk package alone was a major contributor to a sharp increase in stock-based compensation expense:

source: Koyfin

In 2018, the board decided Musk needed another package. This one was far bigger: it granted Musk options to buy 12% of the company at the stock price in place at the time of the award. And with Tesla much more mature, the operational milestones were replaced by revenue and EBITDA targets.

Musk got 1% of the company (with the exercise price again equal to the stock price at the time) for every $50 billion in added market capitalization, as long as the added market value was met by improvements in the business.

source: Tesla proxy statement, February 2018

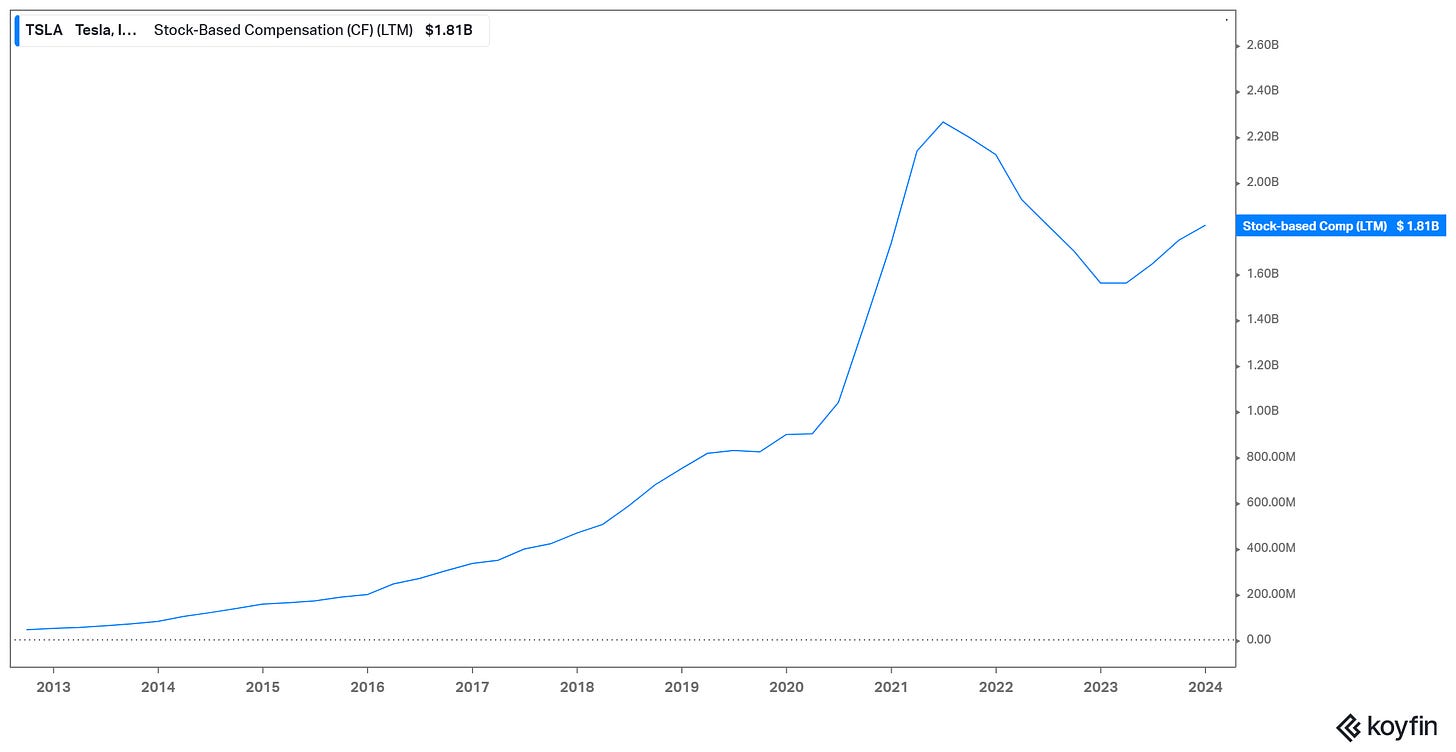

Once again, all the targets were met; Musk wound up receiving options to buy more than 300 million shares at an exercise price just above $23 (both figures adjusted for subsequent stock splits). As recently as late December, that package was worth $72 billion. It’s still worth about $40 billion, even with TSLA down 37% so far this year. Unsurprisingly, that massive package led to a further increase in SBC expense:

source: Koyfin

What Musk’s Package Tells Us

Investors who are skeptical of stock-based compensation will often argue that it is “a very real expense” too often excluded from reported financials. They’re absolutely right that the expense is real.

We can see that in the Tesla packages, which totaled, at the peak TSLA stock price, something like $80 billion in value for Elon Musk. The latter award was invalidated by a Delaware judge in January: she called the grant “unfathomable”.

But Tesla shareholders protested, perhaps rightly, that it wasn’t as if Musk took the money for nothing. At the time of the first equity grant, in 2012, Tesla had a market capitalization just over $3 billion. Four of the ten operational milestones in the first package relate to the production of prototypes. Today, Tesla is worth ~$500 billion, and (for now) remains the unquestioned leader in electric vehicles.

The investors who owned Tesla at the ~$3 billion valuation in 2012 wanted risk. Elon Musk took those risks: as he himself has admitted on multiple occasions, the company nearly went bankrupt, and the launch of the Model 3 in particular was not a preordained success.

Whether Musk’s role in Tesla’s development merits a package worth $56 billion, or $56 million, is up for debate. The inequality created by these types of awards — and broader CEO compensation, which has soared to 350x the salary of the average worker from just 21x — drives political arguments as well.

But, again, Musk’s wealth was only created because Tesla stock went up. Had the company gone bankrupt, the actual stock-based compensation expense would have been zero. That would have been small comfort to shareholders, admittedly. But Tesla shareholders ended up doing exceptionally well, even if they paid Musk dearly for the company’s success.

So, What Does SBC Really Cost?

The split in outcomes (generational wealth for Musk, portfolio-changing returns4 for shareholders) gets to one of the core questions about stock-based compensation: what does it actually cost shareholders?

Again, we get an accounting figure which is a decent approximation of the expense. An investor can think of that figure as an estimate of what the cash compensation would be for the equity being distributed at the time.

But the practical impact isn’t necessarily reflected. Musk’s award is an outlier, certainly: most stock-based compensation is more broadly distributed across employees and issued at levels much more likely (or, in the case of time-vested restricted stock, almost guaranteed) to be reached. As an outlier, though, it provides an interesting case study for how SBC should be viewed.

What Musk’s award truly highlights is that stock-based compensation costs more as the stock goes up. If a company in 2024 pays an employee $100,000 in cash and 10,000 restricted options that vest in twelve months at an exercise price of $10, and the stock doubles to $20, in some sense that employee’s compensation for the year was $200,000.

If the stock gets halved, however, there was compensation booked for that option grant, but it didn’t really cost shareholders anything; the employee won’t exercise, and her practical compensation for the year was actually just the $100,000 in cash received. Similarly, the practical expense of restricted stock is lower if the stock went down, since the company issued shares that, at least according to the market, are worth less.

It’s worth noting that, in extreme cases, GAAP5 accounting for share-based compensation can significantly understate the actual cost. From 2018 to 2021, per filings, Tesla booked $2.2 billion in SBC related to the 2018 Musk award. In 2021 alone, Musk exercised options with an intrinsic value of more than $23 billion.

This creates a somewhat odd dynamic. After all, shareholders (or at least active shareholders) own a company for the upside. Yet — and the Musk award is an amplified example of this — in a company with high stock-based comp, the more upside there is, the more of the upside goes to employees and executives. In this sense, SBC is almost a bit of a downside hedge. Using less cash to pay employees now lessens the need for capital raises and/or the risk of bankruptcy down the line6.

Stock-Based Compensation and Valuation

One of the common themes of this series has been that basic accounting structures are usually good enough. But it’s important to understand the underpinnings of those structures, because sometimes they’re not.

SBC is a good example. For the most part, investors can use the accounting figure to get a sense of how profitable the business actually is. Fundamentally, it does seem like an issue if adjusted operating income is barely above — or less than — the booked amount of share-based compensation.

But sometimes that figure can be misleading — or, at the very least, investors can get to a more accurate estimate of the impact of SBC by going in a different direction. That direction usually involves estimating future dilution based on SBC, and thus accounting for equity issuance in terms of shares outstanding instead of the accounting figure for the expense.

Here, too, Tesla provides a good example. After the release of Tesla’s fourth quarter 2021 report in late January 2022, an investor could have looked at Adjusted EBITDA of $11.6 billion for the year, added back $2.1 billion in stock-based compensation expense, and used $9.5 billion as the ‘true’ EBITDA figure.

Or she could read the 10-K (p. 84), see the $910 million of expense related to the Musk award, and simply add his options to the share count to account for the fact that all of the options would vest. She could then use the remaining ~$1.2 billion to roughly estimate dilution going forward (book expense/market cap is a reasonable proxy, though the K usually gives enough detail to get more specific), and build that rise in share count into her model.

Certainly, the former approach seems easier. And, again, in nearly all cases, it’s good enough. But it’s worth understanding both methods because there are examples where current-year stock based compensation is inflated. One somewhat common instance is when founders get a grant of stock before the IPO: that grant is expensed as share-based compensation over time, though it’s more accurate to simply account for those shares before their expense is booked7. When doing a truly deep dive, it’s not a terrible idea to use both methods — or at least keep an eye out in the 10-K for disclosures that might suggest that the booked method of share-based compensation is understating, or overstating, the case.

Is Stock-Based Compensation Being Ignored?

We noted earlier that SBC has its share of skeptics who believe the market is simply making an error in accepting adjusted figures (nearly all of which exclude stock-based compensation) at face value. It’s not hard to have a little bit of sympathy for their claims.

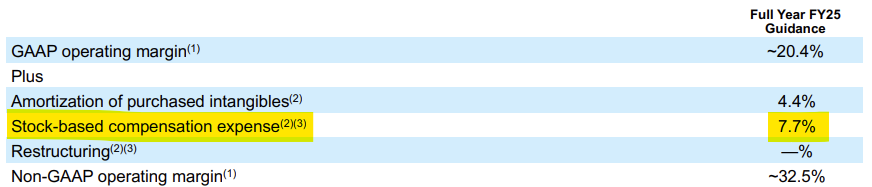

After all, particularly before the 2022 sell-off in tech, many investors, and sell-side analysts, discussed stocks in terms of adjusted earnings multiples which ignore significant dilution. So did management teams — and not just at young, fast-growing companies:

source: Salesforce Q4 FY22 (ending January) earnings release; highlighting by author

For fiscal 2023, Salesforce in March 2022 was guiding for $32 billion in revenue, and still was more than doubling its adjusted operating margin by excluding stock-based compensation. Investors were happily paying more than 40x that adjusted figure — and ~80x adding back stock-based comp — for the stock. Many of those investors pointed to 20% margins as proof of how impressive the underlying business was.

Admittedly, in terms of market cap, the dilution wasn’t quite as significant: Salesforce was worth about $200 billion at the time, so stock-based comp (based on the booked expense, which seems reasonably in line) only created annual dilution of under 2%. Still, that’s a significant headwind to annual shareholder returns.

However, investors worried about stock-based comp were largely shouting into the void. It was precisely these companies — young, fast-growing, tech-focused, using the most SBC — who had the best returns. CRM was one of those names:

source: Koyfin. chart from 3/2/10 to 3/2/22

But as Morgan Stanley noted in the report linked to earlier, a study found that, when controlling for growth and age, high issuers of stock-based compensation in fact underperformed on a risk-adjusted basis. The firm cited another review of sell-side estimates which suggested some analysts (hopefully not those from MS) ignored the impact of dilution in their cash flow models, which unsurprisingly led to more (and perhaps) overly optimistic price targets.

In the two years since tech tanked (and then recovered), stock-based compensationhas become a much bigger point of contention. This is somewhat ironic since the spike in interest rates is credited with starting that sell-off, yet higher rates actually decrease the value of stock options and restricted shares8. Salesforce, like many other companies, has focused on lowering SBC along with other expenses, though equity issuance still clearly has a huge effect on its adjusted numbers:

source: Salesforce Q4 FY24 earnings release (highlighting by author)

In the sense of the broad market, stock-based comp ‘alarmists’, for lack of a better term, have been mostly wrong. They’ve missed out on opportunities. Even CRM stock has roared back, briefly touching a new all-time high last month (with expense control a key reason why).

But skeptics are right that SBC is a real expense. It matters. Dilution impacts shareholder returns, as evidenced by the fact that tech companies like Salesforce are using corporate cash to buy back shares simply to offset the dilution from equity issuance. Obviously, that’s cash that could go to dividends, acquisitions, or buybacks that actually reduce the share count, instead of keeping it flat.

And they may be proven even more correct in the coming years. One of the important questions about stock-based compensation that will be answered amid tighter corporate spending and, perhaps, the next recession is whether the incentives of SBC actually work.

There’s absolutely a possibility in which, particularly in tech, stock-based comp proves to be a “heads I win, tails you lose” proposition for employees relative to shareholders. If the stock goes up, employees and executives profit, and potentially handsomely so. If it goes down, however, the company then has to provide more option awards and/or equity grants to give employees roughly the same value at the new, lower share price.

In that scenario, SBC is not just a real expense, but one that is perhaps bigger than investors, and accountants, have contemplated. That might be enough for the skeptics to finally be vindicated.

As of this writing, Vince Martin has no positions in any securities mentioned.

Disclaimer: The information in this newsletter is not and should not be construed as investment advice. Overlooked Alpha is for information, entertainment purposes only. Contributors are not registered financial advisors and do not purport to tell or recommend which securities customers should buy or sell for themselves. We strive to provide accurate analysis but mistakes and errors do occur. No warranty is made to the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information provided. The information in the publication may become outdated and there is no obligation to update any such information. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a loss of original capital may occur. Contributors may hold or acquire securities covered in this publication, and may purchase or sell such securities at any time, including security positions that are inconsistent or contrary to positions mentioned in this publication, all without prior notice to any of the subscribers to this publication. Investors should make their own decisions regarding the prospects of any company discussed herein based on such investors’ own review of publicly available information and should not rely on the information contained herein.

At Bloomberg, Matt Levine covered the case of Archer Daniels Midland ADM 0.00%↑ executives who were compensated on the operating profit growth in the company’s Nutrition unit. Unsurprisingly, financial shenanigans ensued.

Even that can create a problem. In 2021, the Financial Accounting Standards Board updated its guidance for private companies, in response to not-unreasonable complaints that some of those companies didn’t actually know what their share price was.

From $3.2 billion to $43.2 billion.

Obviously, a great deal depends on when an investor owned TSLA. A not-insignificant percentage of shareholders have lost money since the company went public in 2010. Over the past ten years, TSLA is still a 99th-percentile stock in terms of total returns among U.S. and Canada names, and for those who timed it right (and in size) the gains in some cases were literally life-changing.

Generally Accepted Accounting Principles

This hedge, however, is muted in both directions by tax effects: higher compensation leads to bigger deductions and a lower tax bill, while the opposite is also true.

One example of this is Robinhood HOOD 0.00%↑. As we noted last year, the company actually had take a $485 million charge because the company canceled a previously made grant to the founders.

Higher interest rates mean a higher risk-free rates in the models used to price those awards. Another way to put it is that if the payout is in the future, it’s less valuable when interest rates are higher and those future dollars are thus less valuable (since investors now can earn ~5% in the meantime).